In 2017, the notification rate of tuberculosis in the Northern Region of Portugal was 21.1 cases per 100 000 inhabitants.1 According to the National Tuberculosis Programme Surveillance System (SVIG-TB), poly-resistance to isoniazid and streptomycin (PR-HS) represented 2.6–5% of the cases notified in the Northern Region between 2009 and 2017 Although they represent a relatively low proportion of cases in Portugal, poly-resistances such as PR-HS are precursors to multidrug resistance and, consequently, should be closely monitored.2

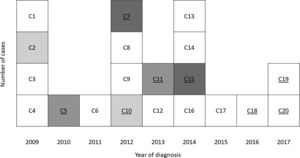

Seventeen cases of pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) with PR-HS were recorded during 2009–2015 in Santa Maria da Feira (SMF), a municipality with 139 312 inhabitants (National Statistics Institute 2011) that belongs to Entre-Douro-e-Vouga-I community health centre cluster (EDVI). This represented a total of 9.3% of the TB notifications in EDVI in this period and was consistently higher than expected in the region (4.1%).

The existence of a cluster of 17 cases with an identical profile of antibacterial resistance led to the generation of the hypothesis of an ongoing TB outbreak. One epidemiological link had been established between two cases, but the remaining cases were apparently not associated. Research was carried out in order to confirm the existence of the outbreak.

Epidemiological surveys performed at the time of notification of PR-HS diagnosed cases from 2009 to 2015 were reviewed by the local Public Health Unit. Cases (or their closest relative alive) were re-interviewed, including clarification of social and occupational history in the two years prior to diagnosis. Specimens of culture-positive cases were sent to the National Mycobacteria Reference Laboratory (INSA) for strain genotyping, using Mycobacterial Interspersed Repetitive Units-Variable Number of Tandem Repeats method (MIRU-VNTR).

All 17 cases included were new cases. Eleven were male (64.7%), with a median age of 50 years (IQR: 22) at the time of diagnosis. All cases had pulmonary involvement, 82.4% were cavitated and 47.1% had positive sputum smear microscopy.

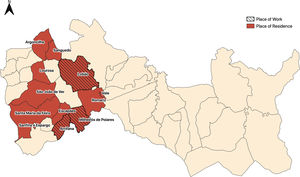

At the time of diagnosis, all cases were resident in SMF. Considering residence and occupation, the review of epidemiological information and the collection of new data made it possible to identify three contiguous parishes (Fig. 1) corresponding to place of residence or work in nine cases (53%).

A median of six people per case were identified for contact tracing (IQR: 3). No cases of active disease were detected and, out of the 146 contacts screened, 12 individuals were diagnosed with latent tuberculosis infection (8.2%). In 15 of the cases only cohabitants were screened, whereas in the other two cases screening involved 22 and 24 contacts at the workplace. No common frequency of social establishments was established.

Two additional epidemiological links were established — two neighbours and two social acquaintances (Fig. 2). Based on the three identified epidemiological links, five specimens were sent to INSA, for analysis through MIRU-VNTR. The five strains had an identical MIRU result, belonging to the Haarlem family.

Three additional HS poly-resistant cases were detected in 2016–2017. All cases belonged to the same previously identified risk area and had an identical MIRU profile. No epidemiological links between these cases were detected nor between these cases and the previous ones. In 2018 and 2019 no new HS poly-resistant cases were reported.

The initial contact investigation failed to identify two epidemiological links that were subsequently confirmed. However, 20–40% of the cases paired by genotyping were not identified during epidemiological investigations,3 either due to insufficient epidemiological investigation or due to the inability/reluctance of patients to identify close contacts.

Lack of routine genotyping hinders the detection of links between cases that have no apparent epidemiological association and consequently the control of community transmission.4 In this instance, the high prevalence of PR-HS should have triggered further investigation at an earlier stage. The proportion of latent tuberculosis infections was also below the threshold expected (up to 15% in the Portuguese population), supporting the hypothesis of unsuccessful contact identification.5

The strain identified belongs to the Haarlem family which is more prevalent in Europe, Central America and the Caribbean, with a known association to resistance and outbreaks.6 So far, there is no knowledge of identical strains in nearby areas, although similar resistance phenotypes in cases not epidemiologically linked were detected in 2011–2013 in bordering parishes — unavailable strains or different genotypic profiles.

Although only eight out of 20 cases reported from 2009 to 2017 in EDVI were genotyped, one has a reasonable degree of suspicion that all cases could belong to the same transmission chain. At this point, two years have elapsed since the last notified case, the most likely period of progression to active disease since a contact with an infectious case.7

Retrospective analysis strongly supports the existence of a long transmission chain of poly-resistant TB in EDVI, partially confirmed by genotyping. The added value of genotyping of specific strains allows the follow-up of disease control and the pinpointing of shortcomings of epidemiological investigations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

CRediT authorship contribution statementB. Gomes: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - original draft. G. Molina-Correa: Investigation. L. Neves-Reina: Investigation. A.C. Oliveira: Investigation, Supervision. R. Macedo Methodology. C. Carvalho: Validation, Writing review & editing. A.M. Correia: Validation, Writing review & editing.