There are scarce data on the routine latent tuberculosis infection treatment (LTBIT) and factors associated with a non-completion in high tuberculosis burden countries. Therefore, in this study we aimed to evaluate the factors associated with non-completion of LTBIT.

Materials and methodsThis was a non-matched case control study conducted at a University Hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. A total of 114 cases and 404 controls were enrolled between January/1999 and December/2009. Cases were close contacts who did not complete the LTBIT and controls were the contacts that completed it. Multivariate analysis was used to investigate risk factors associated with non-completion of LTBIT among contacts in two different periods of recruitment.

ResultsFactors associated with non-completion LTBIT included: drug use (OR 23.33, 95% CI 1.83–296.1), TB treatment default by the index case (OR 16.97, 95% CI 3.63–79.24) and drug intolerance. TB disease rates after two years of follow up varied from 0.4% to 1.9%. The number necessary to treat to prevent one TB case among contacts was 116.

ConclusionsNon-completion treatment by the index case and illicit drug use were associated with not completing latent tuberculosis infection treatment and no tuberculosis disease was identified among those who completed latent tuberculosis infection treatment.

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared tuberculosis (TB) a global public health emergency since 1993, and in 2018, in Brazil 82,409 cases were reported (new and relapses) which corresponds to an incidence rate of 45 cases per 100,000 inhabitants.1 The state of Rio de Janeiro, has the second highest incidence rate in Brazil with an incidence rate of 66.3/100,000 inhabitants, which highlights the importance of actions for TB control and strategies to interrupt the transmission chain.2

Contact tracing of patients with pulmonary TB (PTB) is one of the most important strategies for interrupting the transmission and subsequent development of TB.3 A systematic review found that the prevalence of TB in contacts is 1.4% for high income countries and 3.1% for low/middle income countries.4 In addition, the screening of contacts helps identify contacts with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection (LTBI), through a positive tuberculin skin test (TST) or by interferon gamma release assays (IGRA). Subjects with LTBI have a higher risk of developing TB disease and benefit from the LTBI Treatment (LTBIT). The use of isoniazid (INH) for 6–9 months is recommended for LTBIT with a 60–90% protective effect against active TB.5

The protective effect of INH for LTBIT varies depending on differences in treatment duration and adherence to the scheme.6 Adherence to LTBIT is strongly influenced by clinical, social, financial, and behavioral factors. Studies evaluating factors associated with low adherence to LTBIT under routine conditions are scarce. In high income countries, the proportions of completion of LTBIT vary from 50% to 78%,7–9 and in low/middle income countries, from 54% to 78%.10–12

According to the National TB program (NTP) guidelines, the Hospital TB Control Program in our hospital recommends treatment for LTBI in close contact with PTB patients once active TB is excluded.6,7 In this context, this study aimed to analyze the factors associated with non-completion of LTBIT in contacts with patients with PTB treated at our outpatient clinic.

Material and methodsSettingsThe Hospital TB Control Program was created in 1998 at Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital and has coordinated the TB and LTBI diagnosis and treatment activities. From January 1999 to December 2009, INH was prescribed during 6 months (300mg/die tablets in adults, and 10–15mg/kg/die in children), following the National TB Guidelines for LTBIT.5,6

Study design and study populationWe included all contacts for whom LTBIT was recommended during the study period. In an unmatched case control study design, cases were defined as contacts who did not complete 6 months of LTBIT (contacts that started and stopped treatment at any time) and as controls the contacts who completed 6 months of LTBIT. The sample size was based on the number of contacts recruited by the TB control program. Contacts who were transferred to other Health Units or Clinical Research Unit, before starting LTBIT were excluded. The Investigational Review Board at the Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital granted a waiver for the study and gave ethical approval for publication of the results.

Data collection proceduresData was collected by the researchers using data sources from the Hospital TB Control Program (medical charts and special forms used since 1998). This study evaluated two periods: January 1999 to March 2003 and April 2003 to December 2009. In the first period, the criteria for LTBIT initiation were: (i) contacts with PTB patients aged <15 years, not vaccinated with BCG and with TST≥10mm; (ii) contacts aged <15 years, vaccinated with BCG and with TST≥15mm; (iii) contacts with positive booster response (a second TST≥10mm with an increase in induration of at least 6mm); (iv) HIV positive contact regardless of TST result; (v) immunocompromised contacts due to immunosuppressive drugs use or immunosuppressive diseases with TST≥5mm; (vi) contacts with recent tuberculin conversion (TSTC). TSTC was defined as an increment of TST≥10mm in respect to previous testing in non-BCG-vaccinated contacts, or ≥15mm in contacts vaccinated with BCG in the previous two years.13

In the second period, the criterion for TST positivity changed and LTBIT was recommended to contacts of any age with TST≥5mm.

TB disease was assessed using the National Information System for Notifiable Diseases (Sistema de Informação de Agravos de Notificação – SINAN) records. Names and birth dates of contacts were matched with the SINAN database two years after LTBIT recommendation. In Brazil, access to TB treatment is only possible through the public health system. The TB case is notified and the patient's data (sociodemographic and clinical) are entered in SINAN. Therefore, the contact who developed active TB and initiated anti-TB treatment had his/her data entered in SINAN. We cannot ignore, however, that cases of untreated subclinical TB have occurred. SINAN evaluation was carried out by a professional assigned by the Health Secretary of Rio de Janeiro State. All data were extracted and directly entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

Using special forms developed by the Hospital TB Control Program, the following variables were identified: co-morbidities, chronic medication use, signs/symptoms of drug intolerance to INH (rash, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain, arthralgia, peripheral neuritis, euphoria, insomnia, drowsiness, anxiety, headache, acne, fever), illicit substance use.

Statistical analysisMain outcome measures were proportion of contacts completing LTBIT (adherence to the LTBIT), variables associated with non-completion of LTBIT, TB disease rate and the number of LTBIT needed to prevent one TB case among contacts. Initially, bivariate analysis between contacts who did and those who did not complete LTBIT and each of the potential determinants of treatment default was performed and the differences in proportion were analyzed by Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests and odds ratios (OR) with correspondent 95% confidential intervals are presented.

The variables analyzed were: sex, age, literacy, family income, occupation, origin, type of contact, co-morbidities, previously treated TB, alcohol use, illicit drug use, use of other medications, drug intolerance, drug-resistant TB in the index case (IC), non-completion treatment by the IC and the IC in clinical research. Following the National TB Guidelines, HIV testing was not routinely offered to contacts, thus the HIV status was known only if the contact informed us during the interview. In this case, it was included as a comorbidity.

Variables associated with non-completion in bivariate analysis (p≤0.05) were tested in multivariate models. Adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals for the odds ratio were estimated. To calculate the number of contacts to be treated for LTBI necessary to prevent one TB case (NNT), all contacts who started but did not complete treatment (incomplete LTBIT) or who did not start treatment were considered contacts without LTBIT that had a chance to develop TB disease and all contacts that completed LTBIT were considered contacts with LTBIT who also could develop TB disease. Analyses were performed using Epi-Info (Centers for Disease Prevention and Control, CDC, Atlanta), Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 20.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad.

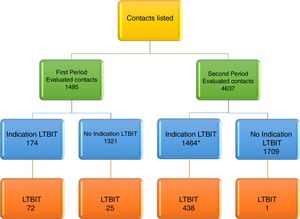

ResultsAccording to inclusion and exclusion criteria, in the first period and in the second period, 11.6% (174/1495) and 46.1% (1464/3173) had LTBIT recommended, respectively. Among 174 contacts with LTBIT indication in the first period, 72 (41.4%) started the treatment. In the second period, among 1464 contacts with LTBIT indication, the following were excluded: 33 (2.3%) due to transfer to other health units at the physician's discretion or due to request by the contact and 998 (68.1%) were referred to a clinical trial linked to TB Trials Consortium, but among them, 250 (17.1%) came back to the Hospital Tuberculosis Program. After the exclusions, 683 remaining contacts with LTBIT indication, 438 (64.2%) started the treatment. By medical decision, another 25 contacts with LTBI in the first period and 1 contact in the second period started on LTBIT although they did not have criteria for this according to NTP, totaling 536 contacts (Fig. 1).

We enrolled 114 cases and 404 controls in the study; for 18 contacts we were unable to retrieve information from Hospital TB Control Program forms. The proportion of contacts that did not complete LTBIT increased from 10.3% (10/97) in the first period to 23.7% (104/439) in the second period (Table 1). In the first period, among cases and controls, females and household contacts were, respectively, 80% (8/10) and 56% (44/79), and 80% (8/10) and 81% (64/79). Median age was 12 years among cases and 10 years among controls. Ninety percent (9/10) of cases and 78% (62/79) of controls had 0 to 8 years of schooling.

Latent tuberculosis infection treatment outcomes in first and second periods.

| Outcomes | First periodn (%) | Second periodn (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Favorable | ||

| Completed treatment | 79 (81.4%) | 325 (74.0%) |

| Unfavorable | ||

| Non-completion treatment | 10 (10.3%) | 104 (23.7%) |

| Tuberculosis disease | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Transfer to another health unit | 5 (5.2%) | 4 (0.9%) |

| Death | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Suspension by the physician | 2 (2.1%) | 5 (1.1%) |

In the analysis of clinical and epidemiological factors associated with non-completion of LTBIT we found that individuals who use illicit drugs were more likely to treatment default (OR 23.33, 95% CI 1.83–296.1, p=0.05), which maintained after fitting the data through multivariate analysis (adjusted OR 0.04, 95% CI 0.00–0.54). However, the small number of drug users among contacts (only 3) produced an imprecise estimate with a large confidence interval (Table 2).

Clinical and epidemiological factors associated with completion of latent tuberculosis infection treatment in first period

| First period | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not completed treatmentn=10n (%) | Completed treatmentn=79n (%) | ||||

| Type of contact | |||||

| Extra-domiciliary | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (11.4%) | |||

| Intra-domiciliary | 8 (80.0%) | 64 (81.0%) | – | 1.0 | |

| Unknown | 2 (20.0%) | 6 (7.6%) | – | – | |

| Comorbiditiesa | |||||

| Yes | 2 (20.0%) | 5 (6.3%) | |||

| No | 8 (80.0%) | 74 (93.7%) | 0.27 (0.04–1.62) | 0.35 | |

| Previously treated tuberculosis | |||||

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.5%) | |||

| No | 9 (90.0%) | 73 (92.4%) | – | 1.0 | |

| Unknown | 1 (10.0%) | 4 (4.8%) | – | – | |

| Alcohol use | |||||

| Yes | 1 (10.0%) | 1 (1.3%) | |||

| No | 7 (70.0%) | 70 (88.6%) | 0.10 (0.00–1.77) | 0.38 | |

| Unknown | 2 (20.0%) | 8 (10.1%) | – | – | |

| Illicit drug use | |||||

| No | 6 (60.0%) | 70 (88.6%) | |||

| Yes | 2 (20.0%) | 1 (1.3%) | 23.33 (1.83–296.1) | 0.05 | 0.04 (0.00–0.54) |

| Unknown | 2 (20.0%) | 8 (10.1%) | – | – | |

| Use of other medicationsb | |||||

| Yes | 1 (10.0%) | 6 (7.6%) | |||

| No | 9 (90.0%) | 73 (92.4%) | 0.73 (0.07–6.86) | 1.0 | |

| Drug intolerancec | |||||

| Yes | 2 (20.0%) | 20 (25.3%) | |||

| No | 6 (60.0%) | 58 (73.4%) | 0.96 (0.18–5.18) | 1.0 | |

| Unknown | 2 (20.0%) | 1 (1.3%) | – | – | |

| Drug resistant tuberculosis in index case | |||||

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.5%) | |||

| No | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (3.8%) | – | 1.0 | |

| Unknown | 10 (100%) | 74 (93.7%) | – | – | |

| Non-completion treatment by index case | |||||

| No | 8 (80.0%) | 67 (84.8%) | |||

| Yes | 1 (10.0%) | 4 (5.1%) | 2.09 (0.20–21.11) | 1.0 | |

| Unknown | 1 (10.0%) | 8 (10.1%) | – | – | |

In the second period, females were 56% (58/104) of cases vs. 57% (187/325) among controls and household contacts were %, and 56% (58/104) and 60% (196/325). Median age was 13 and 17 years among cases and controls, respectively. Years of school were ≤8 for 71% (74/104) of cases and 67% (318/325) of controls. Using bivariate analysis, the following clinical and epidemiological factors were associated with non-completion of treatment: co-morbidities (OR 2.09, 95% CI 1.13-3.89, p=0.01), use of other medications (OR 3.54, 95% CI 1.48-8.48, p=0.002), absence of drug intolerance (OR 2.46, 95% CI 1.39-4.35, p=0.001) and TB treatment default by IC (OR 16.97, 95% CI 3.63-79.24, p=0.00005). However, after fitting the data through multivariate analysis, only the absence of drug intolerance (adjusted OR 2.46, 95% CI 1.39-4.35) and TB treatment default by IC (OR 9.37 95% CI 2.24-39.13) were independently associated with non-completion of LTBIT (Table 3).

Clinical and epidemiological factors associated with completion of latent tuberculosis infection treatment in the second period.

| Factors | Second period | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not completed treatmentn=104n (%) | Completed treatmentn=325n (%) | ||||

| Type of contact | |||||

| Extra-domiciliary | 36 (34.6%) | 113 (34.8%) | |||

| Intra-domiciliary | 58 (55.8%) | 196 (60.3%) | 0.92 (0.57–1.49) | 0.76 | |

| Unknown | 10 (9.6%) | 16 (4.9%) | – | – | |

| Comorbiditiesa | |||||

| Yes | 14 (13.5%) | 80 (24.6%) | |||

| No | 90 (86.5%) | 245 (75.4%) | 2.09 (1.13–3.89) | 0.01 | 0.90 (0.38–2.09) |

| Previously treated tuberculosis | |||||

| Yes | 1 (1.0%) | 5 (1.5%) | |||

| No | 101 (97.1%) | 319 (98.2%) | 0.63 (0.07–5.46) | 1.0 | |

| Unknown | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (0.3%) | – | – | |

| Alcohol use | |||||

| Yes | 7 (6.7%) | 36 (11.1%) | |||

| No | 95 (91.3%) | 288 (88.6%) | 1.69 (0.73–3.93) | 0.21 | |

| Unknown | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (0.3%) | – | – | |

| Illicit drug use | |||||

| No | 101 (97.1%) | 320 (98.5%) | |||

| Yes | 1 (1.0%) | 4 (1.2%) | 0.79 (0.08–7.16) | 1.0 | |

| Unknown | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (0.3%) | – | – | |

| Use of other medicationsb | |||||

| Yes | 6 (5.8%) | 58 (17.8%) | |||

| No | 98 (94.2%) | 267 (82.2%) | 3.54 (1.48–8.48) | 0.002 | 0.37 (0.10–1.31) |

| Drug intolerancec | |||||

| Yes | 17 (16.3%) | 109 (33.5%) | |||

| No | 83 (79.8%) | 216 (66.5%) | 2.46 (1.39–4.35) | 0.001 | 2.46 (1.39–4.35) |

| Unknown | 4 (3.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | – | – | – |

| Index case in clinical study | |||||

| Yes | 17 (16.3%) | 56 (17.2%) | |||

| No | 87 (83.7%) | 269 (82.8%) | 1.06 (0.58–1.93) | 0.83 | |

| Drug resistant tuberculosis in the index case | |||||

| Yes | 9 (8.7%) | 37 (11.4%) | |||

| No | 36 (34.6%) | 110 (33.8%) | 1.34 (0.59–3.05) | 0.47 | |

| Unknown | 59 (56.7%) | 178 (54.8%) | – | – | |

| Non-completion treatment by index case | |||||

| No | 71 (68.3%) | 241 (74.2%) | |||

| Yes | 10 (9.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | 16.97 (3.63–79.24) | 0.00005 | 9.37 (2.24–39.13) |

| Unknown | 23 (22.1%) | 82 (25.2%) | – | – | – |

Two years after LTBIT recommendation, active TB occurred in 1.0% (1/102) and 0.4% (1/245) of contacts who did not start treatment in the first and the second period, respectively. In the first period, TB disease was not observed among contacts who completed and did not complete the LTBIT. In the second period, no active TB occurred among contacts who completed the LTBIT, but active TB did occur in 1.9% (2/104) of contacts who started but did not complete the LTBIT.

After LTBIT indication in both periods, active TB occurred in 0.6% (2/347) of the contacts who were not treated, there was no active TB among contacts who completed the LTBIT and active TB occurred in 1.8% (2/114) of contacts with incomplete LTBIT (Table 4).

Development of tuberculosis disease two years after LTBIT recommendation.

| Development of TB disease up to two years later | Total | NNT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | n (%) | n (%) | |

| First period | ||||

| LTBITa | ||||

| Recommended but not performed | 101 (99.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 102 (100%) | |

| Complete | 79 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 79 (100%) | 112 |

| Incomplete | 10 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (100%) | |

| Second period | ||||

| LTBIT | ||||

| Recommended but not performed | 244 (99.6%) | 1 (0.4%) | 245 (100%) | |

| Complete | 325 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 325 (100%) | 117 |

| Incomplete | 102 (98.1%) | 2 (1.9%) | 104 (100%) | |

| Both periods | ||||

| LTBIT | ||||

| Recommended but not performed | 345 (99.4%) | 2 (0.6%) | 347 (100%) | |

| Complete | 404 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 404 (100%) | 116 |

| Incomplete | 112 (98.2%) | 2 (1.8%) | 114 (100%) | |

In the first period, 112 LTBIT were required to prevent one active TB case. In the second period, 117 LTBIT were required to prevent one active TB case. In both periods, 116 LTBIT were required to prevent one active TB case (Table 4).

DiscussionEarly screening and treatment of LTBI in contacts of pulmonary TB cases are among the priorities launched by the End TB strategy.15 And studies that evaluate the factors associated with completion of LTBIT in high TB burden countries become even more relevant.16,17

The proportion of completed LTBIT is variable between authors, Sharma et al. evidenced in a clinical trials conducted in research centers, this value is high (˃90%),18 but in a recent meta-analysis, Alsdurf et al. after evaluating 70 distinct cohorts pointed out several gaps in the diagnostic and treatment cascades; the general estimate is around 50% of people with medical indications completed LTBIT.19

However, under routine conditions, LTBIT completion rates range from 50% to 78%.8–12 LTBIT, for both children and adults contacts of active pulmonary TB patients, has been recommended by PNCT since 2010.20 However, in the IDT-HUCFF hospital complex of UFRJ, LTBIT became a priority target in 1999, after Hospital TB Control Program implementation. Therefore, it was possible to evaluate the impact of LTBIT under field conditions in a high burden urban area. Non-completion LTBIT rates (10.3% in the first period and 23.7% in the second period) were lower than those described in other series.

Evaluating the indication of LTBI treatment, we observed that there was a four times increase in the number of contacts with treatment indication in the second study period. This increase can be explained by the difference of the LTBI criteria used in each study period. The criteria changes included the treatment of adult contacts and TST positivity cut off decrease from 10mm to 5mm since April 2003. Using this TST positivity cutoff, the Hospital TB Program identified a higher number of infected contacts, which could be subjected to LTBIT.

We observed a significant difference in the proportion of contacts who started LTBIT between the first and second period. The increasing number of contacts who started LTBIT in the second study period could be attributed to the beginning of a clinical trial linked to TB Trials Consortium, in which contacts received incentives and directly observed treatment. These incentives may have had a positive influence on adherence to treatment onset in TB Program. Nevertheless, a majority of contacts did not start LTBIT in either cohort, and the main reason was the refusal of treatment.

The low percentages of non-completion of LTBIT observed in our study were similar to those reported by Codecasa et al., in Italy, and by Mendonça, in Rio de Janeiro and lower than the rates reported in the USA, Canada and in the state of Bahia, Brazil.8,10–12 In Italy, where the study was performed under routine conditions, involving adults from risk groups for active TB, only 21.6% of contacts did not complete LTBIT.9 Our study also found illicit drug use to be an important risk factor for non-completion of LTBIT, and our data are similar to a study conducted in Portugal that highlights the abuse of illicit drugs as well as alcohol for increased risk failure to complete LTBIT.21 Mendonça observed a non-completion rate of 25% among subjects aged under 15 years of age who were treated in a reference unit from 2002 to 2009.12 In large series in the USA and Canada, higher rates of non-completion of LTBIT were reported (40–52%).9,22 In Salvador, Brazil, 46.5% of children and adults contacts did not complete LTBIT.10

Several studies have reported risk factors associated with non-completion of LTBIT. In the USA and Canada, Pettit et al. observed that among adults who initiated INH, female sex and alcohol use were independently associated with LTBIT discontinuation due to drug intolerance.23 In another study, Horsburgh et al. identified the following as risk factors for non-completion of LTBIT: nine months treatment with INH, living in a nursing home, shelter, or prison; illicit drug use, age ≥15 years, and being a health care professional.9 Our study also found illicit drug use to be an important risk factor for non-completion of LTBIT, despite the small sample analyzed. Machado et al. identified the presence of drug intolerance and the need to take two buses to reach the hospital as risk factors for non-completion of LTBIT.10

In contrast to the observations of Machado et al., we found that the absence of drug intolerance was a risk factor for a non-completion LTBIT.10 A possible reason for this finding could be the differentiated care offered by the Hospital TB Program's multidisciplinary team in the presence of drug intolerance, positively influencing the adherence to LTBIT and encouraging contacts not to abandon the treatment. However, this association may be biased as drug intolerance prevalence was low and all cases fulfilled the minor criteria, which do not usually lead to non-completion of LTBIT. Maciel et al., when analyzing different risk groups who had undergone LTBIT, observed the following factors to be associated with LTBIT default: being a health care professional, HIV positive, and a contact of a TB patient. Being a contact of TB patient increased the odds of non-completion of LTBIT by 2.65-fold and, possibly, the concentration of family efforts around the care of patient with TB disease leads to a lower priority given to LTBI.11

In our study, non-completion of TB treatment by the IC was associated with non-completion of LTBIT in the second study period. In this period, the contacts who underwent LTBIT were referred from other Health Units where IC were treated. Default of treatment by the IC possibly had a negative effect on the priority given by their contacts to LTBIT.

In neither period, two years after enrollment in the study, were there any cases of TB disease among contacts who completed LTBIT. On the other hand, TB disease was found in 1.8% of contacts who did not start LTBIT and 0.6% of those who started but did not complete it. In New York city, Anger et al. reported similar results, with higher TB disease rates among contacts who did not start LTBIT (1.5%) than among contacts who started LTBIT (0.4%).24 In Brazil, in other series involving contacts with LTBIT indication, slightly higher rates of TB disease were described, ranging from 2.3% to 3.2%.14,25

The low rates of TB disease found in our study may be due to reasons other than the efficacy of INH therapy itself. Among these, we can cite: (a) hospital setting in a metropolitan area from middle income country, (b) contacts living in a urban area have lower risk for TB development (2.1–2.8%), as cited by Blok26, (c) shorter follow-up period (2 years after the LTBIT recommendation), compared to the other series that followed-up contacts for 5 years.14,25

Overall, the NNT was similar in both periods. Therefore, it was not possible to state in which of the two cohorts the recommendation for LTBIT was more appropriate. Anger et al. observed results slight lower than to the ones found in our study, with 88 LTBITs required to prevent one TB case.24

The main limitations of the present study include the differences in the screening cascade of contacts in the two study periods, the limited sample size (particularly in the first study period) that could have precluded the emergence of other significant associations, the use of secondary data to diagnose TB disease among contacts, and no qualitative or economic analysis carried out to evaluate the barriers for implementation and impact of LTBIT.

ConclusionsWhen analyzing the variables associated with non-completion of LTBIT, we found that illicit drug use and non-completion of TB treatment by the IC were the main risk factors. TB disease rates among contacts who did not start LTBIT or who started and did not complete it were lower than described in the literature and treatment completion of LTBIT may be a protective factor against the development of active TB. The high NNT observed in both periods among contacts who attended a university hospital from urban area suggests that LTBIT may have lower relevance than expected in preventing a TB case.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors thank the PCTH professional team for the access granted to the health information of the contacts and to the professionals of the Health State Secretary of Rio de Janeiro for providing SINAN-TB data.