Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome is a rare and severe adverse drug reaction, occurring generally about two to eight weeks after the introduction of a causative drug.1 Cutaneous involvement usually begins with a morbilliform eruption, with cutaneous edema, mainly involving the face, upper trunk, and extremities, spreading from the face to the entire body, with edema of the face being a characteristic finding. Other cutaneous manifestations include vesicles, pustules, erythroderma, and purpuric lesions.2 DRESS syndrome can be accompanied by different systemic symptoms including fever, lymphadenopathy, hematological abnormalities, or visceral involvement (kidney, liver, heart, lung, muscle, and even brain). Blood test abnormalities typically persist for several days. DRESS syndrome can be life-threatening and is associated with organ failure, with a described mortality up to 10%, although analysis of prospective data shows a lower mortality rate, around 2%.3 Besides causative drug discontinuation, supportive therapy is generally sufficient and may include antipyretic drugs, systemic antihistamines, and topic corticosteroids. However, in severe cases, with visceral involvement, systemic corticosteroids (0.5–2.0 mg/kg) are usually needed. Aromatic anticonvulsants (e.g. phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital) and sulfonamides are the most frequent drugs associated with DRESS syndrome.3 The authors describe a DRESS syndrome induced by osimertinib, in an advanced EGFR mutated lung cancer patient. This third-generation agent was initially associated with scarce skin toxicity in clinical trials, compared to standard agents. After FLAURA trial results showing higher efficacy of osimertinib compared to standard EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors,4 osimertinib became the first-line treatment of EGFR mutation-positive advanced NSCLC,5 enhancing the number of patients potentially treated with this agent.

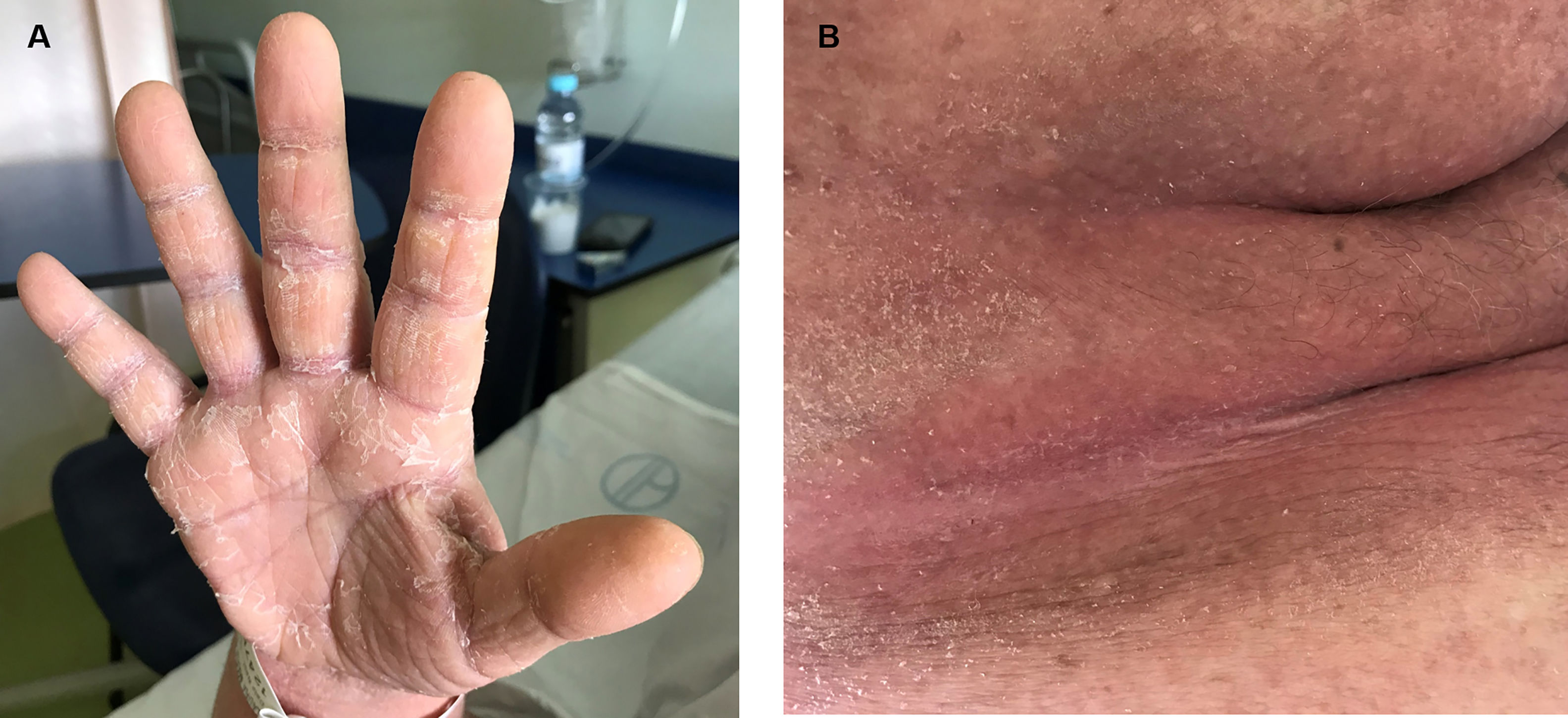

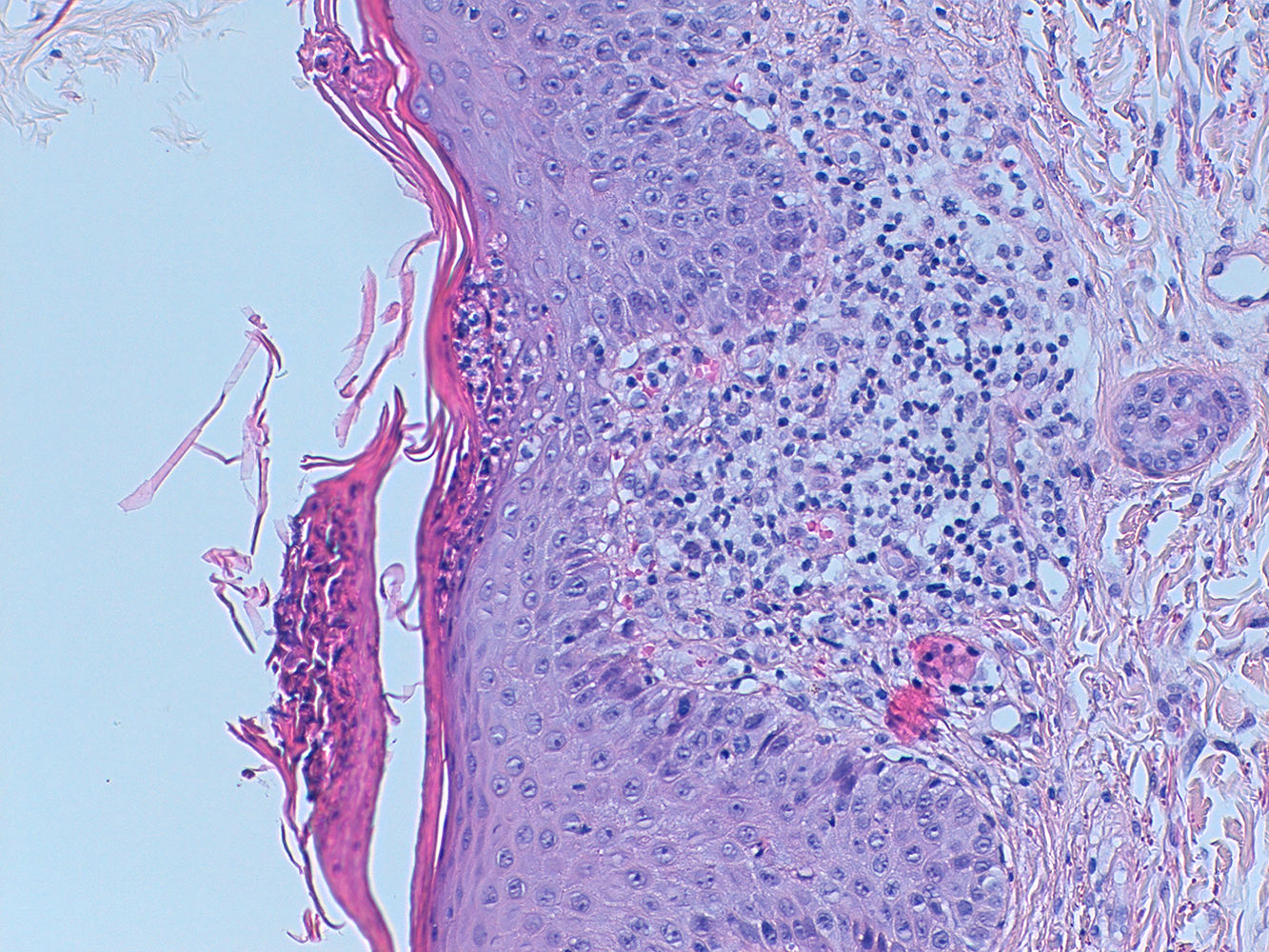

A sixty-year-old woman was initially admitted to the hospital with seizures. The brain scan showed intracranial space-occupying lesions. She started levetiracetam at the end of December 2018 and carbamazepine in January 2019. Investigation revealed a stage IV EGFR mutated (deletion on exon 19) lung adenocarcinoma with the involvement of the central nervous system. She was submitted to radiosurgery and she started systemic therapy with osimertinib (80 mg daily), in early March. After eight days, she was admitted to the hospital with a painful and itchy generalized skin rash on face, neck, trunk, and lower limbs, with preserved skin integrity and with no systemic symptoms. Osimertinib induced skin toxicity was assumed and the drug was stopped. She was discharged from the hospital with topic steroid therapy. But, three weeks after osimertinib suspension, she was readmitted to the hospital with widespread erythema, impaired skin integrity, with no mucosal involvement, and accompanied by fever (Fig. 1). Blood tests revealed eosinophilia (1240/μl; 12.7%) with no leukocytosis, acute kidney failure (AKIN II) with ionic changes, and elevation of alkaline phosphatase and lactate dehydrogenase, suggesting DRESS syndrome. She started systemic corticoid therapy (methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg day), teicoplanin, and fluid therapy, with clinical improvement. As skin involvement had worsened after osimertinib suspension, it was thought it could be related to carbamazepine, which was permanently suspended. Thus, after two weeks, with clinical improvement, and under systemic corticoid de-escalation, osimertinib was reintroduced with no evident adverse reaction. The patient remained hospitalized for two more weeks for surveillance. But, eighteen days after osimertinib reintroduction, she was readmitted to the hospital with a severe generalized rash all over the body with epidermal detachment and erosions greater than 30% of body surface area and no mucosal involvement. At that time, her blood tests revealed again a slight eosinophilia (660/μl; 7.3%) with no leukocytosis and acute kidney failure (AKIN II). Osimertinib was stopped again and systemic corticoid was escalated to prednisolone 40 mg daily. Skin biopsy was compatible with DRESS syndrome, showing a superficial dermal lymphocytic infiltrate, with similar counts of CD4+ and CD8+ cells (some granzyme B positive) and no eosinophils (Fig. 2).

Skin biopsy. A lymphocytic infiltrate with some cells with big nuclei with irregular borders is seen at the superficial dermis. CD4+ and CD8+ cells are in an equilibrated number. Some CD8+ cells are positive for granzyme B. No eosinophils are seen. PAS coloration negative. Within an adequate clinic context, this biopsy is compatible with DRESS syndrome.

In September 2019, after de-escalating systemic corticoid and with the resolution of skin lesions and normalized kidney function, she started gefitinib in the second line, with no skin toxicity. Unfortunately, gefitinib was suspended in early November due to disease progression, and the patient was kept under palliative care till the end of life.

The introduction of a new target agent in real-world clinical practice is always challenging as new toxicities may arise as the number of patients treated increases. The particularity of our case is that this skin toxicity was induced by a novel drug, initially reported as less associated with skin toxicity. Further, skin involvement had worsened after osimertinib suspension and the patient was under carbamazepine, a frequently DRESS syndrome associated drug, which made it difficult to associate osimertinib to this clinical situation. It is important to notice that skin toxicity can prevail after discontinuation of a target agent. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of DRESS syndrome induced by osimertinib described in literature till now.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.