Infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis (TB) and the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) relate to environmental factors, understanding of which is essential to inform policy and practice and tackle them effectively.

The review follows the conceptual framework offered by the World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health (defined as “all those material, psychological and behavioural circumstances linked to health and generically indicated as risk factors’ in the conventional epidemiological language”). It describes the social factors behind TB and COVID-19, the commonalities between the two diseases, and what can be learned so far from the published best practices.

The social determinants sustaining TB and COVID-19 underline the importance of prioritising health and allocating adequate financial and human resources to achieve universal health coverage and health-related social protection while addressing the needs of vulnerable populations. Rapid and effective measures against poverty and other major social determinants and sources of inequality are urgently needed to develop better health in the post-COVID-19 world.

Infectious diseases may be conceptualized as ecological, biological and social events given their ability to influence life at several levels and dimensions.1 Some of the social and economic factors that concur to shape human behaviour pose considerable challenges for preventing and controlling infectious diseases.2 Among the most described and explored are population density, setting (urban/rural), and population growth.3–5 Like other well-established infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis (TB), the prevention and control of 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) also relates to environmental factors. To identify these and to assess their association with the features of the COVID-19 pandemic it is essential to inform policy and practice and address this problem in more practical terms.

In the present article, we follow the conceptual framework offered by the World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on Social Determinants of Health, which defines them as “all those material, psychological and behavioural circumstances linked to health and generically indicated as risk factors’ in the conventional epidemiological language”.6 We describe the social factors behind TB and COVID-19, commonalities between the two diseases, and what we can learn so far from the published best practices.7

MethodsA non-systematic search of the English-written scientific literature was carried out on PubMed using the following keywords: ‘social determinants’, ‘COVID-19’ and ‘tuberculosis’. No time restrictions were applied and the selected publication types included clinical trials, observational studies, cohort studies and literature reviews. The information retrieved from the above search was used in the compilation of the present article.

Social factors and TBTB is a chronic infectious disease and is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide. Over a century ago, Virchow recognized it as a social disease7 and, although TB rates worldwide are declining, they remain very high.8 Thus, in this sense, TB continues to be a social disease inextricably linked with poverty.7,9,10

Global TB control and the respective research strategy have during long periods focused mainly on a biomedical approach rather than a socioeconomic response to the epidemic. Even though it may cure millions of people, an exclusively biomedical response has not been enough to eliminate TB. A more holistic approach, addressing not only biomedical responses but also the broader environmental determinants of this disease, is required.11–14

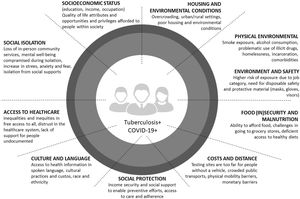

Personal experiences, perceived aetiology of the disease, stigma, beliefs and attitudes associated with TB are meaningful in health-seeking behaviour.15 Many studies have assessed what factors may affect it in different sociocultural settings. Poor perception of health problems, care-associated costs, and physical distance to healthcare facilities are obstacles to seeking care among TB patients.16–18 Furthermore, socioeconomic status, poor housing and environmental conditions, food insecurity and malnutrition, alcohol consumption, smoking, drug consumption, comorbidities (e.g., HIV/AIDS, diabetes, mental disease), and incarceration seem to predispose people to developing TB.

These social factors have been described as influential on the access to TB diagnostic and treatment. A modelling study published in 2018 to support the WHO End TB Strategy demonstrated that reducing extreme poverty and expanding social protection is estimated to reduce TB incidence by up to 84.3%.10

Social factors and COVID-19The outbreak and rapid global diffusion of the COVID-19 continue to occupy prominent positions in social media, research, and policy agendas worldwide.19–21 As expected, and based on previous infectious disease outbreaks, such impacts have been especially dire in particular contexts and particular groups, with broad-ranging and systemic consequences.22–26 In countries everywhere, infection rates of certain diseases are disproportionately high in socially disadvantaged and underserved groups, negatively impacting health and well-being and driving individuals and communities into cycles of illness and poverty.27

Issues such as inadequate health care, especially for poor and low-wage workers without paid sick days or insurance; lack of proper sanitation and infrastructure; and exposure to other diseases, pests, and environmental pollutants, constitute obstacles that can increase vulnerability to infection. Regarding the consequences of the pandemic on individuals and communities, not to mention societies at large, healthcare access, quality, and capacities are fundamental considerations. Protection against income loss is an important enabler for following public health advice, such as staying home when sick or quarantine after exposure, and people living in the context of insecure employment with poor social security have increased risk of both infections and social impact of disease.7,28 Demographic, socioeconomic, and geographical factors that characterize different populations are significant predictors of disease transmission and effects.

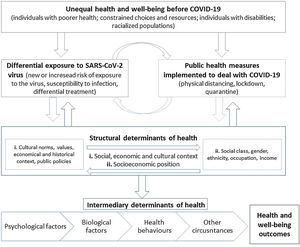

Many social determinants of health – including poverty, physical environment (e.g., smoke exposure, homelessness), and racial and ethnic discrimination – can considerably affect COVID-19 outcomes.29 This way, social determinants have an impact on health by affecting those who get sick and the community as a whole. Not everyone has been equally affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and the same can be affirmed about TB or other infectious disease pandemics. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbates the impact of previous inequalities (Fig. 1), particularly among those already experiencing different types of barriers, like those with TB (Fig. 2). Therefore, mitigating social determinants - such as improved housing, reduced overcrowding, improved nutrition and increased economic and social resilience – diminishes the impact of infectious diseases, such as TB and COVID-19, even before the advent of effective medications.25,30–34

What is there in common between tuberculosis and COVID-19Much had been written in both social media and the scientific literature35–46 before the first cohorts of patients with TB and COVID-19 had been finally evaluated and described.47–51 We are still on the learning curve for COVID-19, while we know more about TB, which has affected mankind for a long time.25 A year into the beginning of the pandemic, COVID-19 has been responsible for roughly the same number of deaths caused by TB annually (approximately 1.8 million for the first vs 1.5 million for the latter in 2019) although COVID-19 as of January 10 2020, had 8 times more cases than TB (approximately 86 million vs 10 million new TB cases in 2019).

They are both airborne-transmitted diseases, although SARS-CoV-2 is more infectious, and therefore needs very careful management of individual protection devices, as well as social distancing.25

Signs and symptoms are largely the same, potentially challenging differential diagnosis. SARS-CoV-2 is also transmitted by asymptomatic individuals, a feature which makes it very transmissible and harder to control.25

For both diseases, co-morbidities lead to increased vulnerability (including cancer; chronic lung and kidney diseases; smoking; alcohol use disorders; depression; HIV and other immunocompromising diseases and diabetes, among others).25

Whilst, for TB, curative strategies are available, with success rates above 85% in drug-susceptible individuals (lower for those who are multidrug-resistant, in the order of 60%), several drugs are under evaluation to define an effective treatment for COVID-19.8,25

Finally, both diseases have significant impact on health and social services and important economic implications, which for COVID-19 still need to be quantified.25 Additionally, scientific literature on the relevance of sequelae following the acute phase of COVID-1951,52 is emerging and those can also be combined with the post-TB treatment sequelae.53–56

Their impact on quality of life, the potential need for pulmonary rehabilitation, and long-term socioeconomic support are future challenges needing further evaluation.

How and what can we learn from good practicesCOVID-19 represents an unprecedented challenge in modern public health practice. Having spread across most of the countries and having infected millions of individuals, this pandemic requires a coordinated, effective response without sacrificing quality or availability of other essential medical services.57 At first glance, COVID-19 transcends the traditional boundaries of socioeconomic and demographic status, with everybody seemingly at risk of falling ill. In reality though, COVID-19 is, like most infectious disease outbreaks, a pandemic that accelerates and compounds existing inequities.

TB infection and prevention programmes, as well as correlative health professionals, are uniquely prepared for this challenge due to all the previous years fighting against this disease. Thus, these resources can and should be leveraged to mobilize already-trained health care workers to adapt existing TB programmes’ guidance; to implement the already available administrative and environmental controls; and to improve practices around the use of personal protective equipment.

Effective epidemic surveillance systems such as increasing mass testing capacity to self-isolate infected patients or implementing effective contact tracing through Bluetooth and/or GPS tracking (as for example Singapore, Portugal and South Korea did) can enable knowledge of infection among asymptomatic individuals.58–60

Individuals need to follow healthy hygiene practices; stay at home when sick; observe physical distancing to lower the risk of disease spread; and use a cloth face-covering or mask in community settings when physical distancing cannot be maintained.32–34 Many countries quickly put in place economic support models to facilitate this, although coverage of such measures is still very limited.61 Here we can see that the concept of community vs individual is really important – if we as individuals comply with the rules, we can protect others.

Another great achievement that needs to be addressed as good practice and capability to response in a time like this is related to the health system preparedness and capacity: building new hospitals; increasing intensive care unit bed numbers; resort to medical and nursing students and/or to retired health care workers.20,24,33 The improvement of community care capacity with hospital at home, distance monitoring with oximeter and home oxygen, are good examples of the capacity and resilience to fight against COVID-19 crisis.

In this sense, both diseases would gain from the use of capacity building efforts; improved surveillance and monitoring systems; and robust programmes and infrastructure already developed over many years of investment.33 An example is one of the TB outpatient centres in the Portuguese Northern Region that actively engaged with the premise of not leaving anyone behind, assembling a significant and rapid response to COVID-19, while ensuring that TB and other essential health services were maintained.62

Lessons learned and global health responseIn recent years, the role of risk factors and social determinants of TB have been more intensively studied and the role of some highly prevalent determinants such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), smoking, diabetes mellitus, alcohol use and under-nutrition have been highlighted. Others include overcrowding, housing conditions and economic deprivation. It has been shown that the highest TB incidence geographic areas are also those with highest incidence of HIV infection, incarceration, overcrowding, unemployment and immigration.

Although TB outbreaks occur everywhere, available diagnosis and treatment ensure that people in richer countries mostly recover from the disease.63 COVID-19, with its current rate of spread, lack of treatment and natural immunity, is exploiting many of the same health, economic, and social inequities that TB has been doing for centuries. Additionally, the prioritization of human and material resources to fight the COVID-19 pandemic and the increased danger of co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 to those with TB pose further threats to TB control efforts.64 If those concerns are not addressed soon, COVID-19 could substantially reverse the gains achieved in TB control and worsen the epidemic in the coming months or years.65,66

To date, the COVID-19 response has demonstrated that, with political will, prioritization and investments, it is possible for the international community to mobilize resources, accelerate scientific discovery, and deploy new public health tools to fight a pandemic.67 These same strategies can thus be employed for TB. However, the COVID-19 response, especially strict lock-downs and mobility restrictions, have also caused immense social and economic suffering and highlighted the need to strike a careful balance between immediate public health gains and unintended health and social side effects.

We have now a rare opportunity to seize the moment and use the attention garnered by this novel virus pandemic to ensure that new investments contribute, not only to the control of COVID-19, but also to strengthen the control of older challenges. Lessons learned from previous relevant public health programs would certainly benefit those at risk for COVID-19.

Final notesDespite the rapidly increasing number of cases, the data needed to predict the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with TB infection and TB sequelae and to guide management in this particular context still lies ahead.

COVID-19, like TB, reminds us of the importance of prioritising health and allocating financial and human resources for universal health and social protection coverage and addressing the needs of vulnerable populations. The link between infectious disease and poverty is further recognised as such; increased investment in their control results in societal structural changes that benefit all if carefully planned and executed.

We need to get ready for the post-COVID-19 world, where people-centred health systems with community-driven interventions will become vital instruments towards achieving better health, economic and moral outcomes.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors contributed substantially to the interpretation of the articles in analysis, critical discussion and revision of the manuscript, and approved its final version.

Financial supportNone declared.

Ethical responsibilitiesNone declared.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.