Balance integrity is critical for an individual’s functional independence. Disruption of balance can cause falls with negative consequences for older adults including loss of autonomy and increased morbidity and mortality.1 Successful maintenance of balance and postural control is a complex skill that requires the integration and coordination of musculoskeletal systems (ie, biomechanics, range of motion, flexibility) and neural systems (ie, motor, sensory, and higher-level pre-motor processes), which must be continuously adapted to suit an array of situations in daily life.2,3

Chronic respiratory diseases stand out as leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) expected to become the 3rd leading cause of death by 2020.4 Chronic respiratory patients (CRP) share risk factors that have been associated with an increased propensity for balance impairment, such as muscle weakness and consumption of multiple medications.5 Among patients with COPD, peripheral muscle impairment, particularly of the lower limbs, is a persistent finding that usually results from or is aggravated by peripheral muscle deconditioning resulting from a reduction in physical activity which is frequently observed in COPD patients.6 Since lower limb muscle strength plays an essential role in balance maintenance it is not surprising that COPD patients frequently report impairments in balance, coordination and mobility.6 Complementary to this explanation, another possible cause for balance impairment in CRP is diaphragm weakness which relates to a core deficit that can disrupt the balance.7

Structured Pulmonary Rehabilitation Programs (PRP) that include exercise training are currently recognised as a core component of the management of CRP. The ever-growing body of evidence among PRP places it indisputably among the most effective therapeutic strategies to improve shortness of breath, health status and exercise tolerance among patients with COPD.8 Nevertheless, balance impairment and specific balance training programs still lack robust evidence, and for the time being are not routinely addressed by most Pulmonary Rehabilitation settings.

Given this we conducted a prospective study among the unselected (real-world) CRP patients referred to our PRP, in order to evaluate balance integrity and to unveil potential demographic, functional and clinical factors associated with balance impairment.

We included all CRP referred to our PRP from September 2017 to December 2018. At baseline all patients were evaluated by a dedicated pulmonologist, responsible for the PRP and aside from patients with known associated neuromuscular diseases and those with gait impairment resulting from osteoarthropathies (in which case, balance impairment could not be undissociated from conditions other than the respiratory disease), all patients were offered the possibility of participating upon written informed consent previously approved by our institution's Ethics Committee.

We collected demographic data, primary diagnosis, number of comorbidities and medication, baseline body mass index, baseline results of pulmonary function tests, distance walked in the six-minute walk test (6MWT), modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale, St. George Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HADS) scores. Balance assessment was performed through the fulfilment of three tests: Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, Tinetti test (TT) and Activities-Specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale. The TUG was used to provide a timed measure of balance and functional mobility in our patients. Briefly, in this test, the patient rises from a standard chair, walks 3 m at a normal pace, walks back to the chair, and finally sits down. Two attempts are made, and the best is recorded. A test duration scored below the upper limit of the 95 % confidence intervals normalised for age can be identified as having a lower performance (impaired balance) (9). The TT consists of 19 items divided into two sections: balance (9 items) and gait (10 items). Individuals scoring less than 26 points are considered to have an increased risk of falling.10 Finally, the ABC scale requires the patient to indicate the degree of confidence, measured in percentage (0–100 %), in performing 16 activities without losing balance or becoming unstable. This test has been previously validated for use within the Portuguese population11 and it is especially beneficial for addressing the efficacy of specific intervention.

Statistical analysis was performed with the software SPSS version 24. Results are presented as medians and range for non-normally distributed continuous variables and as percentage of total for categorical data. Inferential analysis was performed with U-Mann-Whitney test and Pearson chi-square for continuous and categorical variables, respectively, considering a significance level of 5 %.

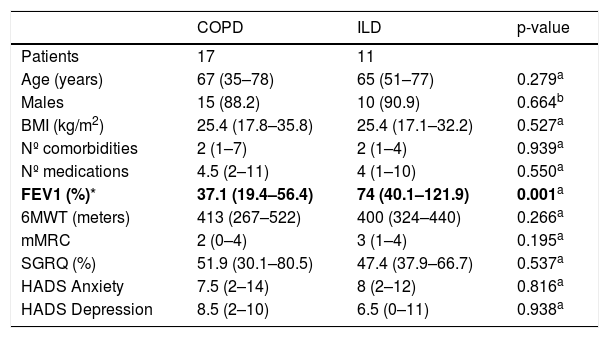

We enrolled 28 patients, mainly male (89.3 %) aged 66 (35–78) years. The most frequent diagnosis was COPD, 60.7 % of patients, followed by interstitial lung diseases (ILD), 39.3 % of patients. The median number of comorbidities was 2 (1-7), and medication was 4 (1-11) per patient. Baseline FEV1 was 47.6 % (19.4–121.9), and the distance walked at the 6MWT was 409 (267–522) meters. The mMRC was equal or superior to 2 in 71.2 % of patients. Median SGRQ was 49.5 % (30.1–80.5), HADS in anxiety 7.5 (2–19) and in depression 7.5 (0–11). Aside from the somewhat expected difference in FEV1, patients with COPD and ILD scored similar results in all of the above measures at baseline (Table 1). The results of the balance tests revealed a TUG of 6.36 (5.15–9.22) seconds, a TT of 26 (22–28) and an ABC scale of 70.63 % (39–94). Of the total, 67.8 % of patients had at least one abnormal balance test.

Baseline characteristics of COPD versus ILD patients.

| COPD | ILD | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 17 | 11 | |

| Age (years) | 67 (35–78) | 65 (51–77) | 0.279a |

| Males | 15 (88.2) | 10 (90.9) | 0.664b |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.4 (17.8–35.8) | 25.4 (17.1–32.2) | 0.527a |

| Nº comorbidities | 2 (1–7) | 2 (1–4) | 0.939a |

| Nº medications | 4.5 (2–11) | 4 (1–10) | 0.550a |

| FEV1 (%)* | 37.1 (19.4–56.4) | 74 (40.1–121.9) | 0.001a |

| 6MWT (meters) | 413 (267–522) | 400 (324–440) | 0.266a |

| mMRC | 2 (0–4) | 3 (1–4) | 0.195a |

| SGRQ (%) | 51.9 (30.1–80.5) | 47.4 (37.9–66.7) | 0.537a |

| HADS Anxiety | 7.5 (2–14) | 8 (2–12) | 0.816a |

| HADS Depression | 8.5 (2–10) | 6.5 (0–11) | 0.938a |

Data are presented as median (minimum-maximum) for non-parametric continuous variables and number (percentage) for categorical variables.

Definition of abbreviations: COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ILD: Interstitial lung disease; BMI: Body mass index; FEV1: Forced expiratory volume at the 1° second; 6MWT: 6-minute walk test; mMRC: Modified medical research council dyspnea scale; SGRQ: St. George Respiratory Questionnaire; HADS: Hospital anxiety and depression scale;

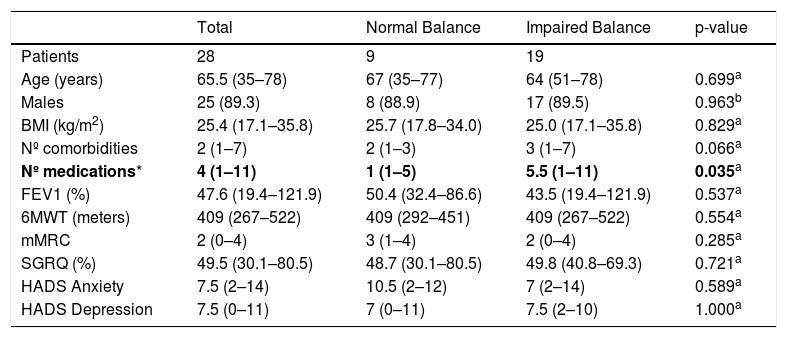

When comparing patients with and without balance impairment, we found no differences in relation to age, gender, body mass index and overall disease severity and functional capacity (assessed by FEV1 and distance walked in the 6MWT). The initial assessment of symptoms and quality of life scores was also similar in both groups. Nevertheless, patients with a higher intake of medications (p = 0.035) were more prone to present balance impairment. Co-morbidities also seemed to influence negatively the presence of balance impairment, but the p-value, though borderline, did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.066). Detailed results are presented in Table 2.

Comparison of patients with and without balance impairment.

| Total | Normal Balance | Impaired Balance | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 28 | 9 | 19 | |

| Age (years) | 65.5 (35–78) | 67 (35–77) | 64 (51–78) | 0.699a |

| Males | 25 (89.3) | 8 (88.9) | 17 (89.5) | 0.963b |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.4 (17.1–35.8) | 25.7 (17.8–34.0) | 25.0 (17.1–35.8) | 0.829a |

| Nº comorbidities | 2 (1–7) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (1–7) | 0.066a |

| Nº medications* | 4 (1–11) | 1 (1–5) | 5.5 (1–11) | 0.035a |

| FEV1 (%) | 47.6 (19.4–121.9) | 50.4 (32.4–86.6) | 43.5 (19.4–121.9) | 0.537a |

| 6MWT (meters) | 409 (267–522) | 409 (292–451) | 409 (267–522) | 0.554a |

| mMRC | 2 (0–4) | 3 (1–4) | 2 (0–4) | 0.285a |

| SGRQ (%) | 49.5 (30.1–80.5) | 48.7 (30.1–80.5) | 49.8 (40.8–69.3) | 0.721a |

| HADS Anxiety | 7.5 (2–14) | 10.5 (2–12) | 7 (2–14) | 0.589a |

| HADS Depression | 7.5 (0–11) | 7 (0–11) | 7.5 (2–10) | 1.000a |

Data are presented as median (minimum-maximum) for non-parametric continuous variables and number (percentage) for categorical variables.

Definition of abbreviations: BMI: Body mass index; FEV1: Forced expiratory volume at the 1° second; 6MWT: 6-minute walk test; mMRC: Modified medical research council dyspnea scale; SGRQ: St. George Respiratory Questionnaire; HADS: Hospital anxiety and depression scale;

When exploring the results per group of pathology, we found that both COPD and ILD patients scored similar results in the balance tests performed at baseline. Due to the low sample size of each individual group, statistical inference could not be performed to unveil individual factors associated with balance impairment per group of pathology.

Our results are in agreement with those of more extensive studies addressing this issue and confirm balance impairment as a frequent finding within CRP.3,6,12 When unveiling potential factors associated with this impairment our results were only positive for the total number of medications in use, regardless of the type of medication. Previous publications on this subject have described a positive association between psychotropic medication use and balance impairment in older and middle-aged adults12–14; which from a conceptual point of view is easier to understand since most of these drugs can have direct effects on balance control. In our sample, we postulate that both the cumulative effect of multiple medications (raising a higher possibility of drug-drug interactions) as well as the overall higher number of comorbidities (which is perhaps the basis of the higher number of medications) can offer an explanation for the higher prevalence of balance impairment in this group of patients, but of course further studies and larger samples are required to confirm this hypothesis.

Due to the limited sample size we could not evaluate the presence of factors associated with balance impairment in each individual pathology group, which would be desirable since ILD and COPD patients have different pathophysiological pathways. Nevertheless we could observe that neither FEV1 nor the distance walked in the 6MWT (two commonly used physiological markers of disease severity) were associated with balance impairment in our sample. On the other hand side, COPD and ILD patients were seemingly comparable in relation to number of medications, the only variable that proved to be associated with increased balance impairment in our analysis.

We acknowledge that our study has some limitations regarding sample size and also the operational characteristics of some of the balance tests utilised. This is particularly important in the specific case of the TUG for which the cut-off used by age can vary significantly from population to population and larger validation studies in our specific population would be desirable.9 To overcome this limitation, we chose to utilise all three balance tests as previously described, but we are aware that there is still a possible slightly biased estimation of balance impairment within our sample.

We are currently preparing to conduct a second phase of this study where we aim to both enlarge the sample size and evaluate the cut-off validation for TUG. In this second phase of the project, we also expect to ascertain the benefits of both standard hospital based PRP as well as specific balance training (as an add-on to standard PRP) in balance-impaired patients.

Nevertheless, we consider that our findings so far, impart an essential message to clinicians dealing with CRP: the careful review of the individual patient´s drug chart should represent an indispensable step of the baseline evaluation, and awareness of overuse of medication should be emphasised as it can contribute to balance impairment.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.