Portugal has managed the first national wave of COVID-19 but now it is now time to turn to other priorities in our Health System. Tuberculosis is our old enemy, while SARS-CoV-2 is the new kid on the block. The slow onset of tuberculosis matches its slow mobilization of resources, in contrast to the speed of SARS-CoV-2. While we are living through a pandemic that, so far, has claimed over 700000 lives worldwide,1 it is easy to forget that TB claims more than 1.2 million lives every year.2

There is international concern regarding the cycle of lockdown and slow restoration of tuberculosis services, predicting an additional 1.4 million TB deaths between 2020 and 2025, due to delayed diagnosis, interruption or delay of treatment.3–6 What can we expect in the next months for tuberculosis incidence in Portugal? The country has been fighting a long war to maintain the incidence under the 20 cases/100.000 inhabitants mark and has a difficult challenge ahead to reach Sustainable Development Goal 3.3 before 2030. It has a unique profile in Western Europe, with an elevated number of cases in natives and a small proportion of cases in foreign-born individuals7 and high spatial heterogeneity transmission associated with housing conditions, unemployment and vulnerable populations.8 The COVID-19 threats are clear: disruption of services and supply chains, access to diagnosis and treatment and the already known consequences of the incoming economic crisis that feeds known determinants of tuberculosis and other infectious diseases.6,9 It is still not clear if COVID-19 and TB co-infection outcomes are relevant or keep on being heavily influenced by age and other known co-morbidities.10

Clinical activities related with tuberculosis were not particularly hard hit in Portugal since they were considered a priority in the Portuguese Health System. However, there was some expected disruption in the access to laboratory and imaging investigations, which will almost surely result in some delays in the time from symptoms to proper diagnosis, a known risk factor for outbreaks.11 On the other hand, investigation of presumptive Covid-19 cases can lead to quicker identification of pre-existing TB,12 although one must keep TB as differential diagnosis amidst overwhelming attention given to Covid-19.

Due to the partial lockdown, we can expect a contrast of influences in TB: increased transmission in home clusters and decreased transmission in social circumstances, particularly social and occupational settings. Respiratory etiquette and social use of masks can break chains of transmission, give the upper hand to the control of this disease and help reduce the impact of delayed diagnosis and maintenance of index case infectiousness.13 Stigma associated to mask usage by tuberculosis patients or visiting health professionals is also something that will certainly diminish in the next few years.

Crisis also offers a broad set of opportunities. The clearest example is digital transition that has advanced more in two months than in the last two years due to the sheer pressure of physical distancing. DOT monitoring and patient follow-up can benefit from this. The long awaited reform of the tuberculosis dedicated health services could also be favored.

There will be other opportunities, such as the present familiarity with contact tracing among the general population, dedication of public health units to core activities of epidemiologic surveillance and infectious disease control, increasing use of digital technologies (with new developments) for the follow up of patients and the side effects of preventive measures for COVID-19 in pathologies like tuberculosis and influenza. In fact, despite their differences there is much to look forward to in the lessons learnt from SARS-CoV-2 and the accumulated experience with TB.14 Tuberculosis outpatient centers will certainly take advantage of telemedicine and electronic tools to guarantee improved access. Online meetings and continuous training will also benefit.

Nonetheless, it is clear that we need to keep on prioritizing the vulnerable group multidisciplinary approach: homeless, social housing populations, inmates. Intersectoral collaborations with NGOs continue to prove crucial. Behind Portugal’s Universal Health Coverage and TB cost-free treatment, social support and poverty reduction measures are the backbone of a sustainable fight against tuberculosis. It is well known that heterogeneity of epidemiology of the disease favor the targeting of high-risk groups, based on a variety of determinants.15

Finally, the expertise of field epidemiology and the pursuit of infectious diseases deserve a proper setting and dedicated multidisciplinary teams to face the myriad of enemies, from the well-known tuberculosis to the new zoonotic threats that can endanger, as we are witnessing, our way of living.

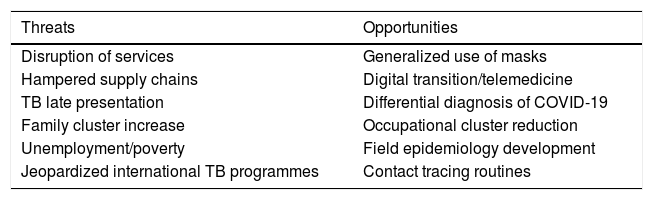

Despite not being able to predict the future, the anticipation of these different threats and opportunities (Table 1) might also help to shape health services and guide clinical, epidemiological and preventive measures. There is a chance that the particular setting of Portugal might help strike a decisive blow in tuberculosis transmission.

Threats and Opportunities in the context of Tuberculosis control in Portugal.

| Threats | Opportunities |

|---|---|

| Disruption of services | Generalized use of masks |

| Hampered supply chains | Digital transition/telemedicine |

| TB late presentation | Differential diagnosis of COVID-19 |

| Family cluster increase | Occupational cluster reduction |

| Unemployment/poverty | Field epidemiology development |

| Jeopardized international TB programmes | Contact tracing routines |

No additional funding sources are to be declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.