Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive fibrotic interstitial lung disease of unknown cause, which predominantly manifests in older males. IPF diagnosis is a complex, multi-step process and delay in diagnosis cause a negative impact on patient survival. Additionally, a multidisciplinary team of pulmonologists, radiologists and pathologists is necessary for an accurate IPF diagnosis. The present study aims to assess how diagnosis and treatment of IPF are followed in Portugal, as well as the knowledge and implementation of therapeutic guidelines adopted by the Portuguese Society of Pulmonology.

Materials and methodsSeventy-eight practicing pulmonologists were enrolled (May–August 2019) in a survey developed by IPF expert pulmonologists comprised of one round of 31 questions structured in three parts. The first part was related to participant professional profile, the second part assessed participant level of knowledge and practice agreement with national consensus and international guidelines for IPF as well as their access to radiology and pathology for IPF diagnosis, and the third part was a self-evaluation of the guidelines adherence for diagnosis and treatment in their daily practice.

ResultsParticipants represented a wide spectrum of pulmonologists from 14 districts of Portugal and autonomous regions of Azores and Madeira. The majority were female (65%), with 5–19 years of experience (71%) and working in a public clinical center (83%). Importantly, the majority of pulmonologists follow their IPF patients (n=45) themselves, while 26% referred IPF patients to ILD experts in the same hospital and 22% to another center. Almost all pulmonologists (98%) agreed or absolutely agreed that multidisciplinary discussion is recommended to accurately diagnose IPF. No pulmonologists considered pulmonary biopsy as absolutely required to establish an IPF diagnosis. However, 87% agreed or absolutely agree with considering biopsy in a possible/probable UIP context. If a biopsy is necessary, 96% of pulmonologists absolutely agree or agree with considering criobiopsy as an option for IPF diagnosis. Regarding IPF treatment, 98% absolutely agreed or agreed that antifibrotic therapy should be started once the IPF diagnosis is established. Finally, 76% stated that 6 months is the recommended time for follow-up visit in IPF patients.

ConclusionsPortuguese pulmonologists understand and agree with national consensus and international guidelines for IPF treatment but their implementation in Portugal is heterogeneous.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic progressive lung disease, which predominantly manifests in adults over 55 years old and tends to affect more men than women.1 The exact prevalence of IPF is unknown with estimates ranging from 2 to 29 people per 100000 in the general population2–4 and is increasing over time.4 The etiology and exact pathophysiological mechanism of the disease is still unknown and the median natural survival of patients with IPF is only 2–5 years from the time of diagnosis.5,6 It is not uncommon for patients to live 5 years or more after receiving the diagnosis but many patients die from progressive respiratory failure.7 Moreover, given the varied natural history of the disease, it is difficult to determine an accurate clinical course for patients with newly diagnosed IPF. Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) is the imaging and histopathological hallmark pattern of IPF contrary to the other idiopathic interstitial pneumonias,8,9 and diagnosis relies on this feature. Obtaining an accurate diagnosis of IPF can be challenging, because symptoms of exertional dyspnea, cough, and fatigue are nonspecific and often attributed to more common medical conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or heart failure.10

IPF was initially considered to be a chronic inflammatory11 process and therefore the first international guidelines on IPF diagnosis and treatment recommended agents to target inflammatory pathways, despite the very low level of evidence supporting this recommendation.12 However, understanding of the pathobiology of IPF has undergone dramatic changes since then, evolving from an inflammatory process to an aberrant reparative response to alveolar epithelial cell injury, causing irreversible loss of function.13,14 Several clinical trials addressed the efficacy of compounds targeting the fibrotic process but turned out to be disappointing.15,16 The following 2011 guideline represented a rigorous joint effort by the American Thoracic Society (ATS), European Respiratory Society (ERS), Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS), and Latin American Thoracic Society (ALAT), which did not strongly recommend any pharmacological treatments for patients with IPF.3 A new updated guideline was published in 2015 considering current alternative therapies17 such as nintedanib and pirfenidone and a year later, a consensus document for the diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis was published by Sociedade Portuguesa de Pneumologia, Sociedade Portuguesa de Radiologia e Medicina Nuclear and Sociedade Portuguesa de Anatomia Patológica.18 This document envisioned increasing awareness among, not only pulmonologists and specialists in interstitial lung diseases, (ILDs) but also general practitioners of the importance of early diagnosis of the disease19 and the challenge of new approved drugs. More importantly, experts recommended that the evaluation of benefits and risks of the therapeutic strategy as well as the clinical behavior of the disease should be undertaken in each individual patient. Further on, in 2018, a new collaborative recommendation guideline was updated regarding IPF diagnostic criteria.20

Along with the clear evolution of IPF management strategy, this study aims at contributing to guidelines disclosure and to evaluate whether the current information on IPF treatment and diagnosis is adequate and implemented by Portuguese pulmonologists according to the Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALA Clinical Practice Guideline and the Portuguese consensus document.

Material and methodsStudy designA one-round, anonymous, cross-sectional survey was conducted comprised of on a line 31-item questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed to characterize current clinical practice patterns regarding the diagnosis and treatment of IPF patients by pulmonologists, considering the knowledge about national consensus18 and international guidelines.20 It comprised three parts. The first part included 10 questions about demographic characteristics and professional profile, such as years working as a health care professional, location of working center, monthly and yearly volume of patients followed, reference or not of patients to an ILD expert within or outside the hospital, and time between visits. The second part was a 4-question self-evaluation of the level of IPF diagnosis and treatment guidelines acceptance and practice. The third part was a group of questions to access the level of agreement with specific national and international recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of IPF, according to the clinical practice in relation to IPF management. This last part of the survey contained 17 multiple-choice questions with five unique response options.

Data were collected from 78 pulmonologists across Azores, Madeira and 14 districts in mainland Portugal, between May and August 2019. Since 33 pulmonologists refer their patients to a colleague, the remaining 45 were included for further statistical analysis.

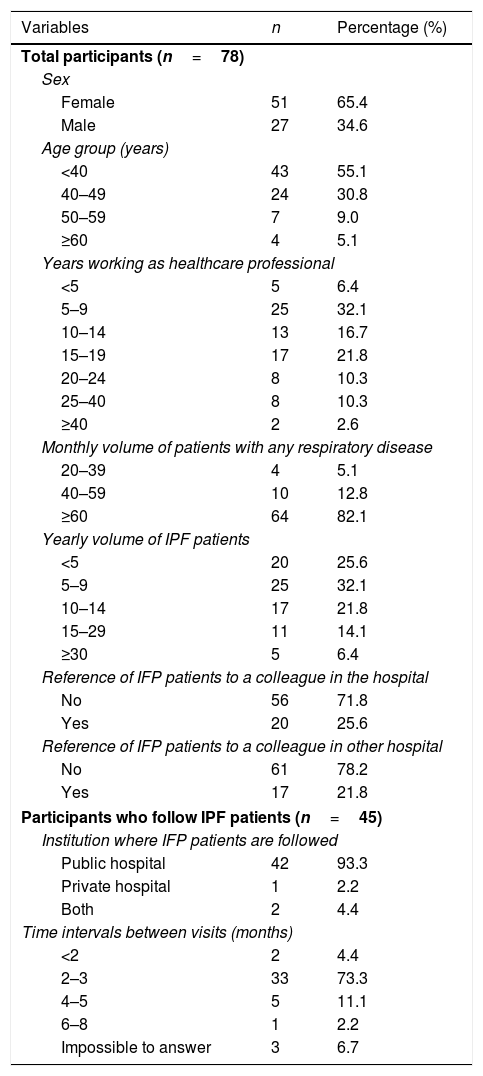

ResultsOf the total pulmonologists enrolled in this study, 65.4% were female (Table 1). The age among participants varied, with 55.1% of the respondents being under 40 years old and 30.8% between 40 and 49 years old. In terms of clinical experience, 32.1% of participants have worked as healthcare professionals for 5–9 years and 21.8% for 15–19 years. The majority of participants (82.1%) attend ≥60 patients per month with different respiratory diseases, while 42.3% follow more than 10 IPF patients per year. Fifty-eight percent (n=45) of participants do not refer their IPF patients, whereas 25.6% refer IPF patients to an ILD expert in the same department and 21.8% to an ILD expert in another hospital (Table 1). Of the 45 pulmonologists who follow IPF patients, the majority (93.3%) follow their patients in a public hospital and 73.3% follow their patients every 2–3 months.

Participant sociodemographic characteristics and professional status.

| Variables | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total participants (n=78) | ||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 51 | 65.4 |

| Male | 27 | 34.6 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| <40 | 43 | 55.1 |

| 40–49 | 24 | 30.8 |

| 50–59 | 7 | 9.0 |

| ≥60 | 4 | 5.1 |

| Years working as healthcare professional | ||

| <5 | 5 | 6.4 |

| 5–9 | 25 | 32.1 |

| 10–14 | 13 | 16.7 |

| 15–19 | 17 | 21.8 |

| 20–24 | 8 | 10.3 |

| 25–40 | 8 | 10.3 |

| ≥40 | 2 | 2.6 |

| Monthly volume of patients with any respiratory disease | ||

| 20–39 | 4 | 5.1 |

| 40–59 | 10 | 12.8 |

| ≥60 | 64 | 82.1 |

| Yearly volume of IPF patients | ||

| <5 | 20 | 25.6 |

| 5–9 | 25 | 32.1 |

| 10–14 | 17 | 21.8 |

| 15–29 | 11 | 14.1 |

| ≥30 | 5 | 6.4 |

| Reference of IFP patients to a colleague in the hospital | ||

| No | 56 | 71.8 |

| Yes | 20 | 25.6 |

| Reference of IFP patients to a colleague in other hospital | ||

| No | 61 | 78.2 |

| Yes | 17 | 21.8 |

| Participants who follow IPF patients (n=45) | ||

| Institution where IFP patients are followed | ||

| Public hospital | 42 | 93.3 |

| Private hospital | 1 | 2.2 |

| Both | 2 | 4.4 |

| Time intervals between visits (months) | ||

| <2 | 2 | 4.4 |

| 2–3 | 33 | 73.3 |

| 4–5 | 5 | 11.1 |

| 6–8 | 1 | 2.2 |

| Impossible to answer | 3 | 6.7 |

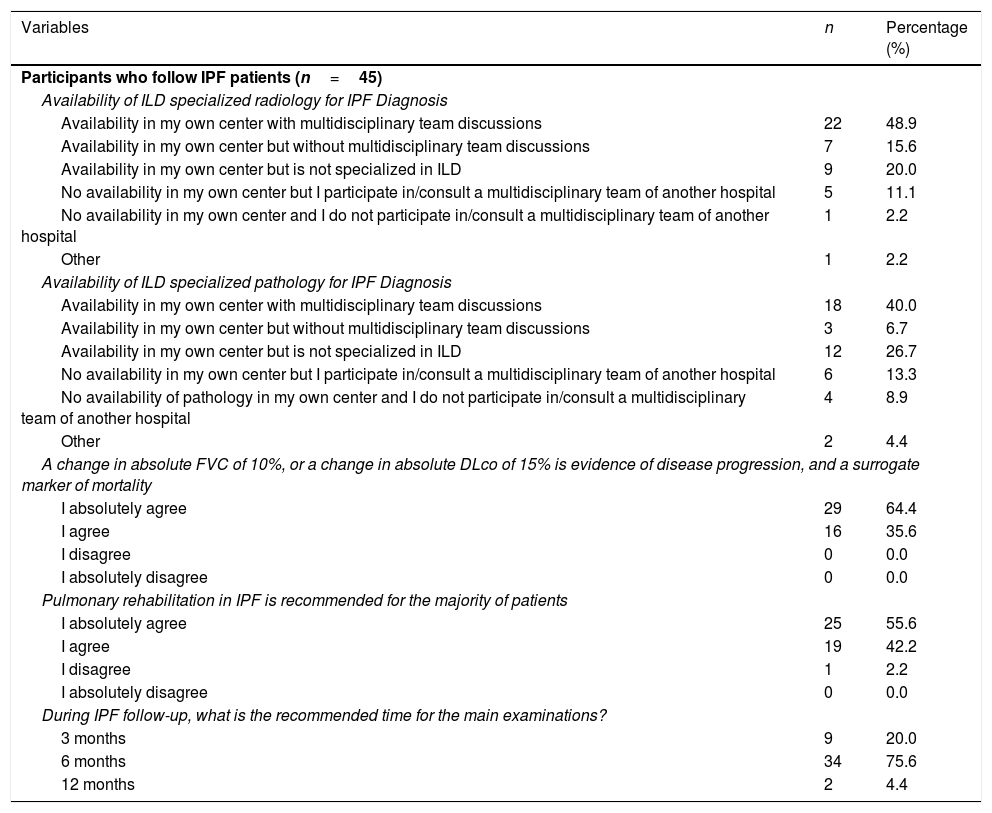

Pulmonologists were also asked about the availability of ILD specialized radiology and pathology as well as multidisciplinary team discussions for IPF diagnosis (Table 2). Approximately half (48.9%) of pulmonologists following IPF patients have ILD specialized radiology with multidisciplinary team discussions in their hospital center and 40.0% have ILD specialized pathology with multidisciplinary team discussions in their hospital center.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis management.

| Variables | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Participants who follow IPF patients (n=45) | ||

| Availability of ILD specialized radiology for IPF Diagnosis | ||

| Availability in my own center with multidisciplinary team discussions | 22 | 48.9 |

| Availability in my own center but without multidisciplinary team discussions | 7 | 15.6 |

| Availability in my own center but is not specialized in ILD | 9 | 20.0 |

| No availability in my own center but I participate in/consult a multidisciplinary team of another hospital | 5 | 11.1 |

| No availability in my own center and I do not participate in/consult a multidisciplinary team of another hospital | 1 | 2.2 |

| Other | 1 | 2.2 |

| Availability of ILD specialized pathology for IPF Diagnosis | ||

| Availability in my own center with multidisciplinary team discussions | 18 | 40.0 |

| Availability in my own center but without multidisciplinary team discussions | 3 | 6.7 |

| Availability in my own center but is not specialized in ILD | 12 | 26.7 |

| No availability in my own center but I participate in/consult a multidisciplinary team of another hospital | 6 | 13.3 |

| No availability of pathology in my own center and I do not participate in/consult a multidisciplinary team of another hospital | 4 | 8.9 |

| Other | 2 | 4.4 |

| A change in absolute FVC of 10%, or a change in absolute DLco of 15% is evidence of disease progression, and a surrogate marker of mortality | ||

| I absolutely agree | 29 | 64.4 |

| I agree | 16 | 35.6 |

| I disagree | 0 | 0.0 |

| I absolutely disagree | 0 | 0.0 |

| Pulmonary rehabilitation in IPF is recommended for the majority of patients | ||

| I absolutely agree | 25 | 55.6 |

| I agree | 19 | 42.2 |

| I disagree | 1 | 2.2 |

| I absolutely disagree | 0 | 0.0 |

| During IPF follow-up, what is the recommended time for the main examinations? | ||

| 3 months | 9 | 20.0 |

| 6 months | 34 | 75.6 |

| 12 months | 2 | 4.4 |

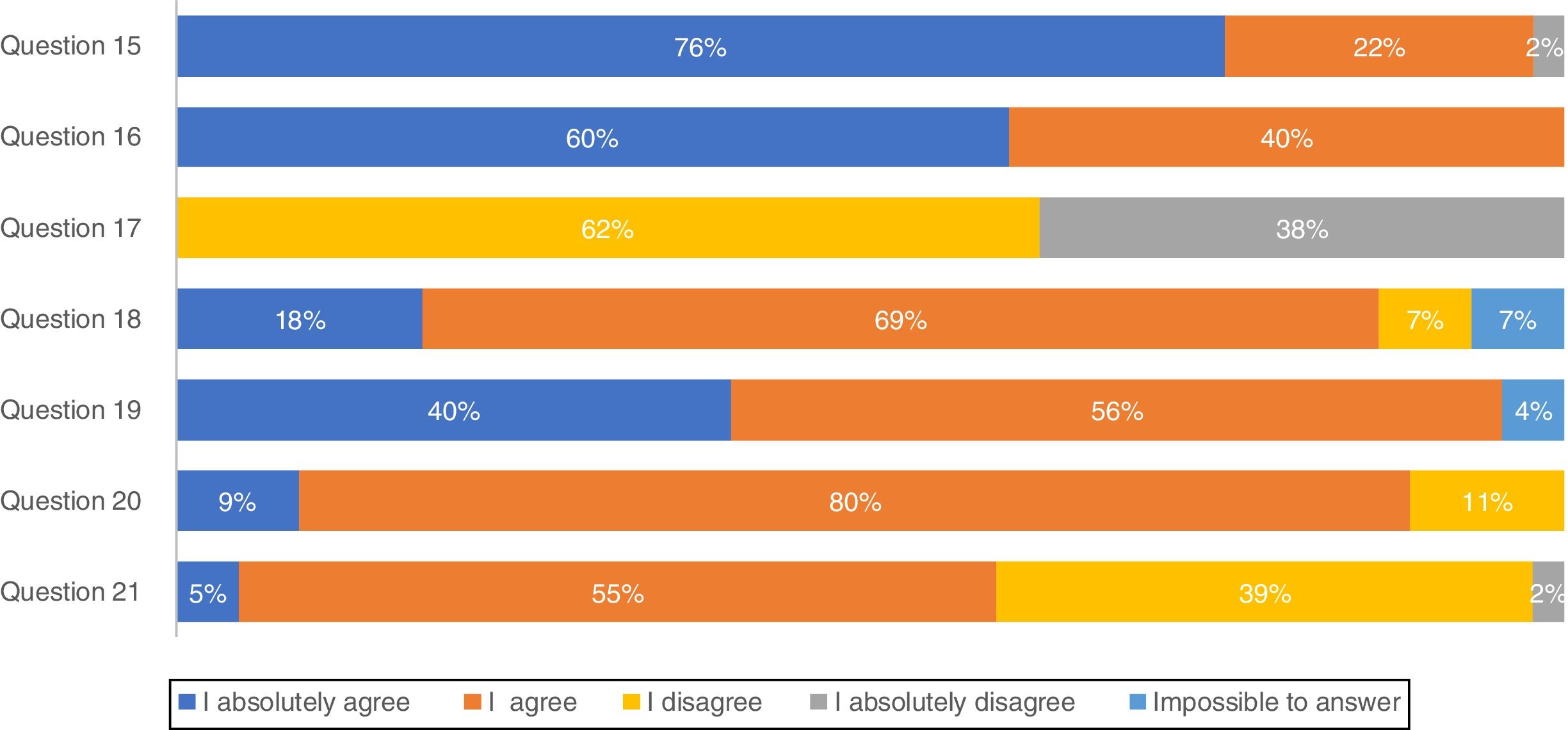

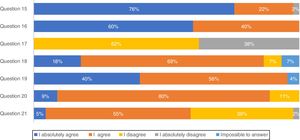

Most pulmonologists (71.1%) reported to have a high knowledge of national consensus and international guidelines and 66.7% consider those recommendations in clinical practice (results not shown). These considerations were further evaluated through a list of questions regarding IPF diagnosis (Fig. 1). The majority of professionals (75.6%) absolutely agree with multidisciplinary discussion with experienced clinicians, radiologists and pathologists, to accurately diagnose IPF. More than half of the respondents (60.0%) absolutely agree with high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) as the main procedure for IPF diagnosis, while 62.2% disagree and 37.8% absolutely disagree that pulmonary biopsy is absolutely required. However, if a biopsy is required, 40.0% absolutely agree and 55.6% agree with criobiopsy as a valid option to establish IPF diagnosis. Most participants (80.0%) agree with the term probable usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), while approximately half (54.5%) agree with the term possible UIP. Upon IPF suspicion, 77.8% absolutely agree to use serologic testing for connective tissue disease screening.

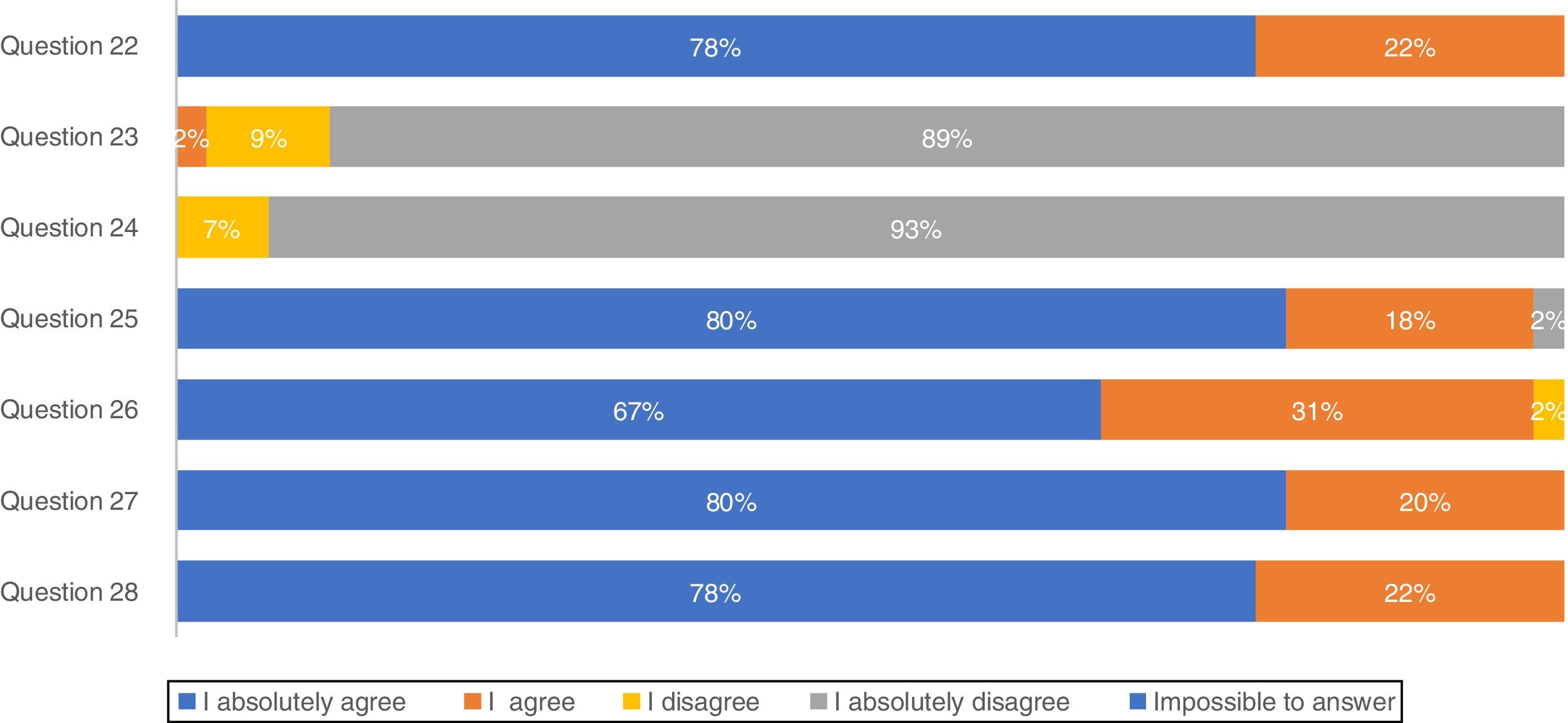

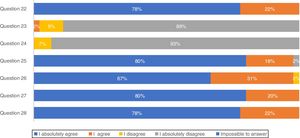

Concerning treatment, the majority of participants (88.9%) absolutely disagree that IPF patients should be treated with corticosteroid monotherapy to prevent treatment-related morbidity, as well as 93.3% absolutely disagreeing with combination therapy of N-acetylcysteine, azathioprine, and prednisone for IPF patient treatment (Fig. 2). In total, approximately 80% of pulmonologists absolutely agree that antifibrotic treatment has benefits for important patient outcomes, Importantly, 66.7% of pulmonologists absolutely agree that antifibrotic therapy should start once IPF diagnosis is established.

Considering IPF management (Table 2), responses varied among pulmonologists. More than a half (64.4%) absolutely agree that disease progression in IPF is defined as a sustained decline of more than 10% in forced vital capacity (FVC) and/or of 15% in diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO). In addition, 55.6% absolutely agree that pulmonary rehabilitation in IPF is recommended for the majority of patients, long-term oxygen therapy should be provided to patients with clinically significant resting hypoxemia, and the patients with the defined criteria should undergo lung transplantation. Following initiation of IPF treatment, 75.6% consider that 6 months is the recommended time for main appointments.

DiscussionThis survey represents the first assessment of clinical practice of Portuguese pulmonologists regarding IPF diagnosis, management and treatment, considering the knowledge of the recent national consensus18 and international guidelines.3,20 Despite the wide age range among participants, the selected population is generally young and mostly female and 60% of the participants had more than 10 years of clinical practice. The number of IPF patients attending a monthly/yearly appointment is indicative of a high level of clinical practice. The public hospital appears to be the main care setting for most IPF patients followed by pulmonologists in this survey.

Due to the challenge in reaching a confident IPF diagnosis caused by nonspecific symptoms, guidelines suggest using multidisciplinary teams from different specialties.21–23 The panel is completely in line with this concept since 76% absolutely agree and 22% agree that a multidisciplinary team including experienced clinicians, radiologists and pathologists as the main process for an accurate diagnosis. Indeed, our results showed that nearly half of the practitioners have multidisciplinary team discussions with specialized radiology and/or pathology available in their institution or in another hospital center. However, a considerable number of participants in the present study admitted that these specialties were not available in their own centers. This delay in IPF diagnosis and further treatment in Portugal24 is a cause for concern.

Seventy-one percent of pulmonologists that follow IPF patients reported they have a high level of knowledge of IPF national consensus and international guidelines for IPF diagnosis and treatment and 66.7% apply their knowledge in clinical practice. This level of familiarity implies that IPF awareness is a priority within national health programs, which is true considering the number of programs boosted by the national policies. However, the remaining 28% of participants who are not aware of recommendations may hinder their intervention in clinical practice.

There was some unexpected controversy regarding the use of HRCT as the main procedure for IPF diagnosis with opinions divided among pulmonologists. A confident diagnosis of IPF can be made in the correct clinical setting when HRCT imaging shows a pattern of typical or even probable UIP in a certain context.3,17,18,20,25 Indeed, the official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Statement on IPF3 states that a correct IPF diagnosis requires “the presence of a UIP pattern on HRCT in patients not subjected to surgical lung biopsy (SLB)”. Importantly, for patients with newly detected ILD of apparently unknown cause who are clinically suspected of having IPF and have an HRCT pattern of UIP, it is strongly recommended not to perform SLB.20 Surprisingly, only 37.8% of participants in this study absolutely disagree with the sentence “A pulmonary biopsy is absolutely required to establish an IPF diagnosis”. On the other hand, ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guidelines suggest SLB in a probable UIP context; 68.9% of participants agreed with the sentence “Do you consider biopsy in a possible/probable UIP context?” The remaining 40% are more in line with Fleishner Society white paper statement that does not require lung biopsy in a probable UIP in an appropriate clinical setting.23 The fact that the majority of the panel tends to consider lung biopsy by name in possible UIP contexts may be due to the high level of non-IPF fibrotic ILDs in our country, with particular relevance of the high frequency of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis related with exposure to birds and molds.26,27 Considering biopsy as an alternative, lung cryobiopsy although still controversial has been shown to be generally safe and well tolerated.28 Tomasseti et al. demonstrated that the proportion of IPF cases diagnosed with a high degree of confidence increased from 16 to 63% after performing lung cryobiopsy and in some cases led to a change in the diagnostic suspiction.28 A recent prospective, multicentre study evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of transbronchial lung cryobiopsy (TBLC) for ILD diagnosis. The results showed good agreement between TBLC and SLB obtained sequentially from the same patients, supporting the clinical utility of TBLC as an alternative to SLB for patients requiring lung tissue for ILD diagnosis.29 Moreover a comparative study between TBLC and explant lungs from lung transplantation of patients with UIP showed also a high concordance.30 According to this survey, Portuguese pulmonologists globally agree with the use of this technique as an option for IPF diagnosis.

The recommendations against outmoded therapies for IPF are established, as there is strong evidence against their use.31 Portuguese pulmonologists absolutely disagreed (95.3%) with triple therapy which is fully compatible with international guidelines.3 Apart from this, respondents of this survey totally agreed that antifibrotic treatment benefits IPF progression and should be started as soon as this disease is diagnosed. Lung transplantation has been used as an option for IPF treatment worldwide for patients with moderate to severe disease32 as well as by Portuguese pulmonologists, but mortality is high and one of the potential reasons for this is a late referral of the patients to the transplant units with advanced disease.33

Most of participants responded that the time for IPF patients’ follow-up and main examinations was every 6 months, this result differs from guidelines in which the range is 3–6 months. Paradoxically, the majority of the participants stated that the usual appointments of IPF patients in their clinical practice was exactly 3 months. More importantly, palliative care is rarely instituted in patients with IPF before the end of life,7 which should be addressed in our care facilities.

This study presented some potential limitations that should be addressed to avoid misinterpretation of results. First, in the initial part of the questionnaire, 33 participants were eliminated from the study since they referred IPF patients to another colleague. To avoid this statistical pitfall, we could have considered this as the first question. Second, we could have reached a higher number of participants with a telephone-based interview survey or a face-to-face interview. Moreover, this is a cross-sectional study therefore it cannot support conclusions on casual relationships. However, it allowed the analysis of the main concerns regarding IPF management, diagnosis and treatment. In the future, a large-scale survey across all Portuguese geographical areas is needed to confirm the consistency of responses regarding the knowledge of IPF recommendations and further clinical practice.

ConclusionsTo the best of our knowledge, this survey represents the largest and most comprehensive assessment of the level of awareness and acceptance of IPF National Consensus and international Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT IPF Guidelines. More importantly, we conclude that most IPF recommendations are followed by Portuguese pulmonologists, but their implementation is heterogeneous.

Conflicts of interestFunding informationThe study and medical writing support for the manuscript was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Portugal.

The authors thank Maria João Almeida (Pulso Ediciones) for editorial assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.