To estimate the cost-effectiveness of omalizumab compared with standard of care in the treatment and control of severe persistent asthma, using the outcomes from the Portuguese subpopulation of the eXpeRience registry.

MethodsThis was a pragmatic cost-effectiveness analysis based on real world data from the eXpeRience registry which recruited 62 patients with uncontrolled persistent allergic asthma from 20 participating centers in Portugal. Response to omalizumab treatment was measured prospectively up to 24 months by the physician’s Global Evaluation of Treatment Effectiveness (GETE). Retrospective data on patients’ clinical symptoms, asthma control, lung function, exacerbations, and healthcare utilization were available for up to 12 months before omalizumab initiation and served as the standard of care comparator. The number of exacerbations (severe and non-severe), the number of clinical episodes, the number of days absent from work and/or school, and GETE response to therapy were considered as effectiveness outcomes. Following a societal perspective, as cost indicators, both direct and indirect costs were considered. Direct costs relate to the cost of omalizumab, standard of care and clinical episodes (emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and unscheduled doctor visits). Indirect costs relate to the societal cost of work absenteeism. Unit costs for clinical episodes and drugs were taken from official sources within the Portuguese Health Authority. A univariate sensitivity analysis was performed.

ResultsA rate of 1.5 exacerbations per patient-year was estimated following omalizumab treatment compared with 8.2 exacerbations per patient-year prior to omalizumab initiation, implying an 82.1% reduction in the incidence of exacerbations following omalizumab treatment relative to standard of care alone. A 54.1% reduction in GETE score was also observed in favor of omalizumab treatment. The mean cost per person-year was 3023є in the 12 months of standard of care prior to omalizumab and 16,111є in the period of treatment with omalizumab. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratios were 2244є/exacerbation avoided, and 1750є/unit decrease in GETE classification.

ConclusionOur results demonstrate that adding omalizumab to the treatment of patients with uncontrolled severe persistent asthma reduces the number of exacerbations, improving overall treatment effectiveness at an acceptable cost from a societal perspective.

Asthma is one of the most common chronic non-communicable diseases in the world, affecting an estimated 339 million people of all ages as of 2016.1 In Portugal, asthma affects about 6.8% of the population overall, 7.2% of the child/adolescent population (<18 years old), 6.3% of the young/middle-aged adult population (aged 18–65), and 8.0% of the older adult population (>65 years old).2

The emphasis of asthma management is on achieving and maintaining control of its clinical symptoms: wheezing, shortness of breath, coughing, and chest tightness. For the majority of patients, clinical control is typically achieved with the use of low to medium doses of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and long-acting β2-agonists (LABA). A proportion of patients is unable to achieve control despite treatment with high doses of ICS, LABA and, in some cases, even oral corticosteroids (OCS). This group of patients, defined as having severe persistent asthma, has been estimated to constitute 10–20% of all patients with asthma.3 Compared to patients with non-severe persistent asthma, patients with severe persistent asthma are generally at increased risk of asthma exacerbations (severe onset of symptoms), negatively impacting normal daily activities and leading to increased healthcare use.4–6

A Portuguese prevalence-based cost-of illness study found that patients with uncontrolled asthma have a 2-times higher annual cost per patient (895є) compared to controlled patients (425є). The acute care usage cost domain (non-scheduled medical visits, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations) was found to be responsible for 62% of this increase.7 In an Italian study, the total annual cost per patient with severe persistent asthma was estimated to be 3-fold higher than the cost for mild persistent asthma. For severe persistent asthma, indirect costs due to loss of paid workdays were found to contribute 55% to an estimated total annual per patient cost of 3328є, further including drug therapy, general practitioner and other physician visits, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations.4

A substantial proportion of patients with severe persistent asthma have allergic immunoglobulin E (IgE) mediated disease.8 The first approved anti-IgE therapy for these patients is omalizumab, a humanized anti-IgE monoclonal antibody, indicated as add-on therapy to improve asthma control in patients with severe persistent allergic asthma, characterised by frequent exacerbations despite daily use of high-dose ICS and LABA.9

Omalizumab as add-on to ICS-based therapy has been investigated extensively in randomized clinical trials (RCT) in children, adolescents, and adults with persistent allergic asthma. These RCT demonstrated that omalizumab is safe and effective in patients treated with omalizumab as compared to patients receiving placebo.10–16

These results have been confirmed in multiple observational studies.17–21 The eXpeRience registry was a post-marketing, international, non-interventional, observational registry established to evaluate real-world effectiveness and safety of omalizumab.18 Results for the 62 Portuguese patients enrolled in the eXpeRience registry have been discussed in detail.20

Although in the Portuguese subgroup of the eXpeRience registry omalizumab has also proven to be safe and effective,20 to date, nothing is known about its cost-effectiveness from a Portuguese perspective. As such, the objective of this study was to determine the cost-effectiveness of omalizumab as add-on to ICS-based therapy for patients with severe persistent allergic asthma, based on the outcomes from the Portuguese subpopulation of the eXpeRience registry.20

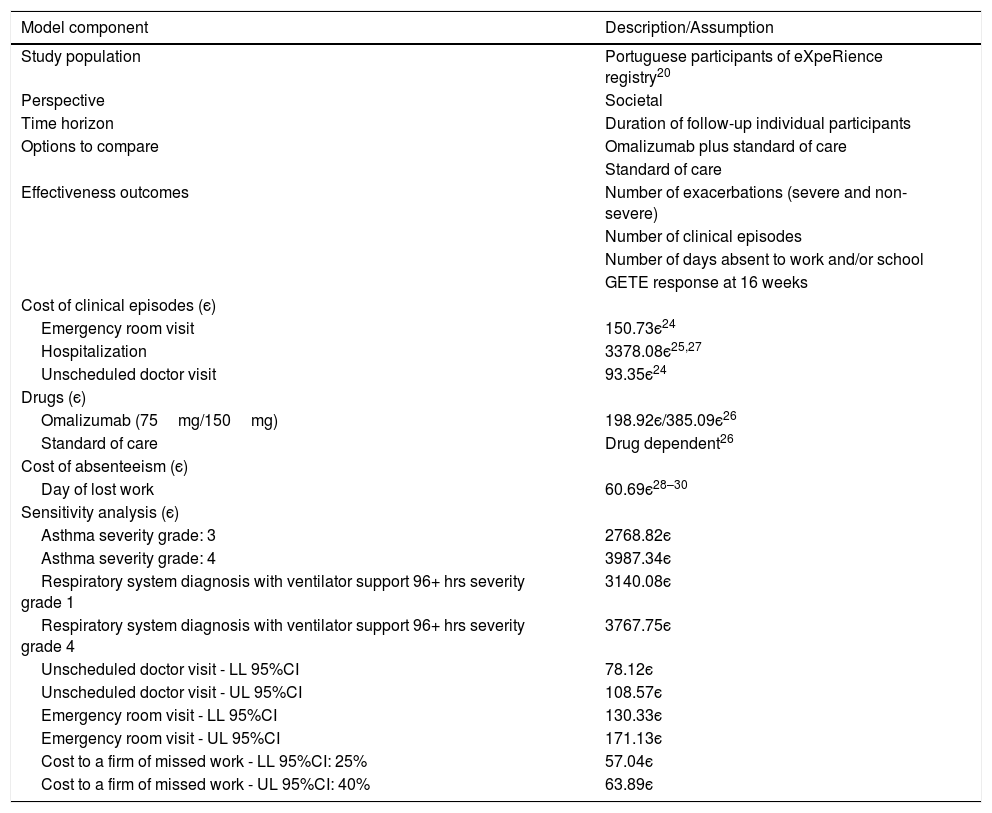

MethodsFollowing the methodological guidelines for studies of economic evaluation of medicines in Portugal22 in force at the time of the analysis, in this study the societal perspective was adopted. As time horizon, the observation period of each patient during the eXpeRience registry study was considered. On average, the observation period was 22 months, with a minimum follow-up time of 3.4 months and a maximum of 37 months (Table 1).

Summary of key model components.

| Model component | Description/Assumption |

|---|---|

| Study population | Portuguese participants of eXpeRience registry20 |

| Perspective | Societal |

| Time horizon | Duration of follow-up individual participants |

| Options to compare | Omalizumab plus standard of care |

| Standard of care | |

| Effectiveness outcomes | Number of exacerbations (severe and non-severe) |

| Number of clinical episodes | |

| Number of days absent to work and/or school | |

| GETE response at 16 weeks | |

| Cost of clinical episodes (є) | |

| Emergency room visit | 150.73є24 |

| Hospitalization | 3378.08є25,27 |

| Unscheduled doctor visit | 93.35є24 |

| Drugs (є) | |

| Omalizumab (75mg/150mg) | 198.92є/385.09є26 |

| Standard of care | Drug dependent26 |

| Cost of absenteeism (є) | |

| Day of lost work | 60.69є28–30 |

| Sensitivity analysis (є) | |

| Asthma severity grade: 3 | 2768.82є |

| Asthma severity grade: 4 | 3987.34є |

| Respiratory system diagnosis with ventilator support 96+ hrs severity grade 1 | 3140.08є |

| Respiratory system diagnosis with ventilator support 96+ hrs severity grade 4 | 3767.75є |

| Unscheduled doctor visit - LL 95%CI | 78.12є |

| Unscheduled doctor visit - UL 95%CI | 108.57є |

| Emergency room visit - LL 95%CI | 130.33є |

| Emergency room visit - UL 95%CI | 171.13є |

| Cost to a firm of missed work - LL 95%CI: 25% | 57.04є |

| Cost to a firm of missed work - UL 95%CI: 40% | 63.89є |

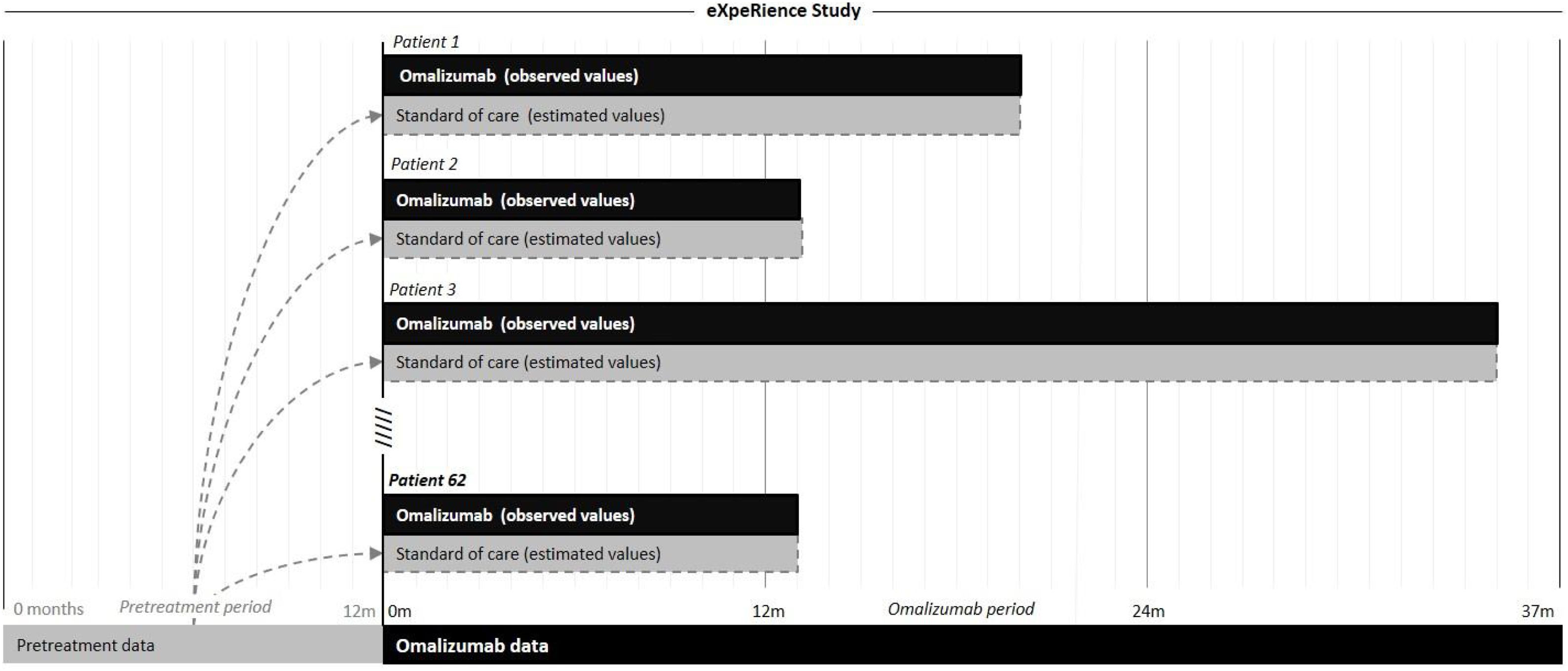

In Portugal, the eXpeRience registry recruited a total of 62 patients with uncontrolled persistent allergic asthma from 20 participating centers. Response to omalizumab treatment, as measured by the physician’s Global Evaluation of Treatment Effectiveness (GETE) is available at approximately 16 weeks after initiation of omalizumab. Further data on patients’ clinical symptoms, asthma control, lung function, exacerbations, and healthcare utilization are available retrospectively for up to 12 months before and prospectively at 16 weeks and possibly 8, 12, 18, and 24 months after omalizumab initiation.17–21 Information on omalizumab and concomitant medication use is available only prospectively in the registry. We performed a pragmatic cost-effectiveness analysis based on data from the Portuguese registry participants, comparing the costs and effectiveness of two treatment alternatives for the management of severe allergic asthma: omalizumab plus standard of care and standard of care alone. A scheme representative of the analysis is presented in Fig. 1.

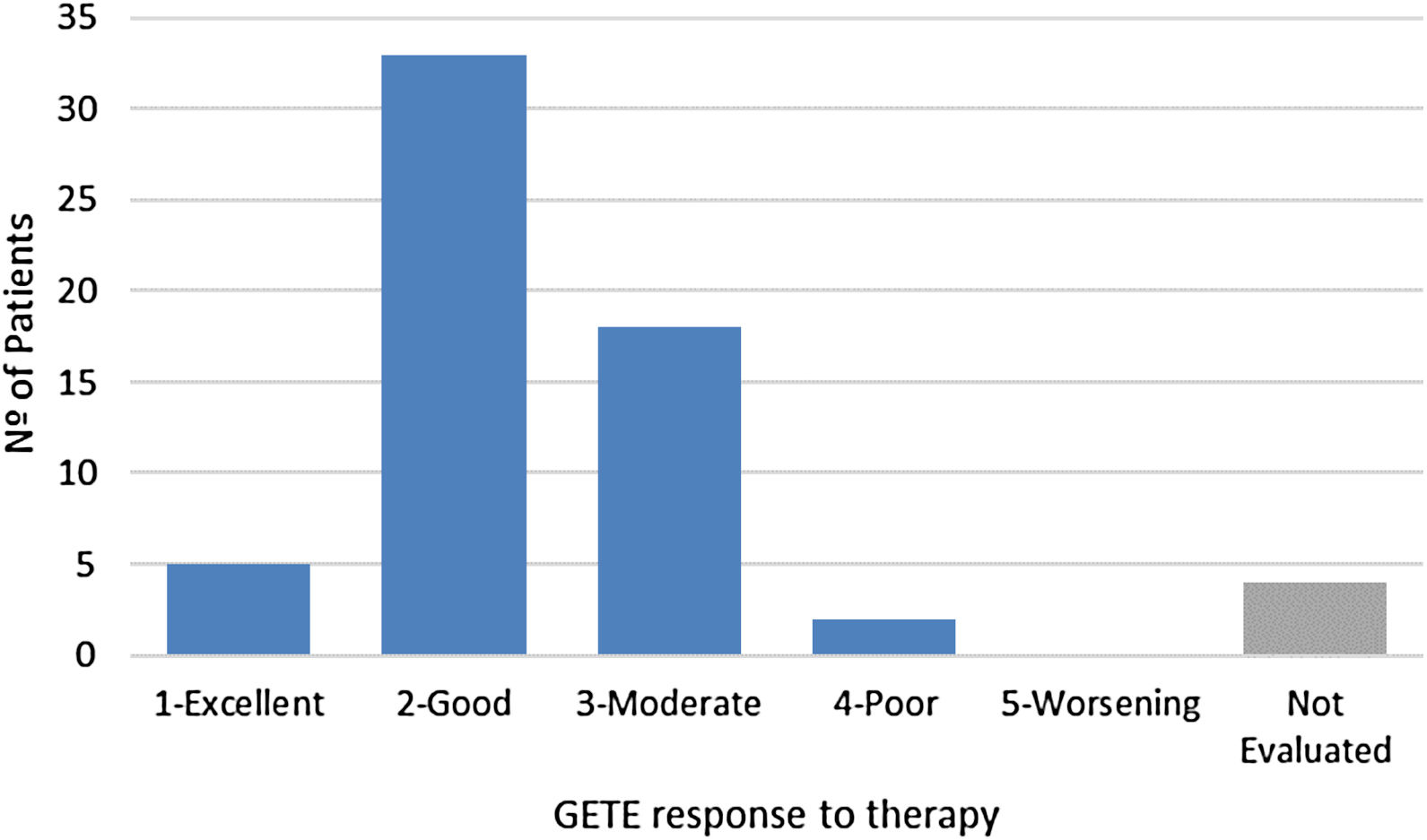

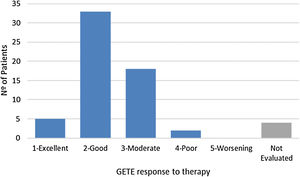

For the omalizumab plus standard of care treatment arm, the total number of exacerbations, clinical episodes (emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and unscheduled doctor visits), and days of absence (work and/or school) observed during the prospective phase of the study, as well as the matching total amount of concomitant medication (standard of care), were available. The patient-year was calculated by the sum of observation time of each patient. GETE response was considered as observed after approximately 16 weeks of omalizumab initiation, considering a five-point scale: 1-excellent, 2-good, 3-moderate, 4-poor, and 5-worsening.18

For the standard of care treatment arm, to provide a term of comparison, corresponding retrospective data for each individual participant from the 12-month period before initiation of omalizumab was considered. During this period, patients were treated solely with standard of care. Retrospective data was extrapolated to a period equivalent to each participant’s prospective period of the study.

As an example, consider a patient with 5 asthma exacerbations in the pre-omalizumab treatment period (12-months) and a 24-month omalizumab treatment period. In this study for the standard of care treatment arm, a period of 24 months with 10 exacerbations was considered (i.e., the estimated incidence rate in the pre-treatment period was 5 exacerbations/year and applying this rate to a period of time equivalent to the time period of the omalizumab arm, 24 months, gives 10 exacerbations). In a similar way to this example, the incidence rates, based on pre-treatment data, of the other indicators and applied to a period equivalent to the period of treatment with omalizumab were estimated by patient, for the standard of care treatment arm.

Since basal GETE does not exist, it was assumed that without any further change in treatment (e.g. continuing standard of care) the patient´s health would worsen, so counterfactual GETE response on the standard of care at approximately 16 weeks was rated to be ‘5-worsening’ for all participants.

In the absence of retrospective information on standard of care medication, concomitant medication recorded between baseline and the 16-week visit was conservatively used as a proxy.

Missing prospective data up to the final follow-up of each patient were imputed using a last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach, where deemed suitable. No data imputation was performed for retrospective missing data.

Effectiveness and cost outcomesThe number of exacerbations (severe and non-severe), the number of clinical episodes, the number of days absent from work and/or school, and GETE response to therapy were considered as effectiveness outcomes. As cost indicators, both direct and indirect costs were considered, costs are presented in euros, updated to 2017 values.23 Direct costs relate to the cost of omalizumab, standard of care, and clinical episodes (emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and unscheduled doctor visits). Indirect costs relate to the societal cost of work absenteeism.

Unit costs for clinical episodes and drugs (Table 1) were taken from official sources within the Portuguese Health Authority.24–26 The cost per hospitalization was determined as a weighted average of the costs of All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Group numbers APR-DRG 141 (asthma, severity grades: 3 and 4) and APR-DRG 130 (respiratory system diagnosis with ventilator support 96+ hrs, severity grades: 1–4),25 assuming that 7% of asthma related hospitalizations require mechanical ventilation.27 Costs of emergency room visits and unscheduled doctor visits were obtained from the analytical accounting database for hospitals of the Portuguese National Health Service.24 Drug costs were taken from the official drug retail price list.26

The indirect cost of a day of work absenteeism was based on the average monthly gross earnings of employees in Portugal 1097є in 201528), augmented by the employer contribution to Social Security (23.75%29) and the estimated cost to a firm of missed work (33%30).

Cost-effectiveness calculationsFinal results are presented in terms of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICER), representing the additional cost of obtaining one additional unit of effectiveness. Since no imputation of missing data was performed, the ICER related to each effectiveness outcome was calculated based only on participants for whom the necessary retrospective and prospective data was available to calculate the impact of omalizumab on both effectiveness and costs. For the GETE response to therapy, costs were calculated only up to the corresponding visit.

A univariate sensitivity analysis was performed for GETE response and cost parameters (hospitalization costs, emergency room visit costs, unscheduled doctor visit costs, and work absenteeism cost). For univariate sensitivity analysis of GETE was considered a baseline GETE response rated with 3 – “moderate” and 4 – “poor” instead of “5-worsening” for all participants. The different costs of hospitalization, varying according to the different severity grades of asthma and respiratory system diagnosis with ventilator support 96+ hrs and for the remind costs: emergency room visit costs, unscheduled doctor visit costs, and work absenteeism cost the sensitivity analysis was performed changing the costs according to the 95% confidence interval limits.

The analysis was performed with Microsoft Excel (2016).

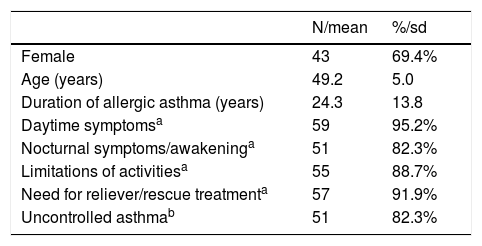

ResultsThe Portuguese subpopulation of the eXpeRience registry enrolled 62 patients—69.4% of which were female—with a mean age of 49.2 years (Table 2). At baseline, the mean duration of allergic asthma was 24.3 years. According to investigator assessment, 82.3% of patients had uncontrolled asthma. Most patients were experiencing symptoms, limitations in activities, and the need for rescue treatment. The average duration of prospective observation of these patients was 22 months.20

Baseline characteristics of Portuguese patients (N=62) in the eXpeRience registry.

| N/mean | %/sd | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 43 | 69.4% |

| Age (years) | 49.2 | 5.0 |

| Duration of allergic asthma (years) | 24.3 | 13.8 |

| Daytime symptomsa | 59 | 95.2% |

| Nocturnal symptoms/awakeninga | 51 | 82.3% |

| Limitations of activitiesa | 55 | 88.7% |

| Need for reliever/rescue treatmenta | 57 | 91.9% |

| Uncontrolled asthmab | 51 | 82.3% |

sd – standard deviation.

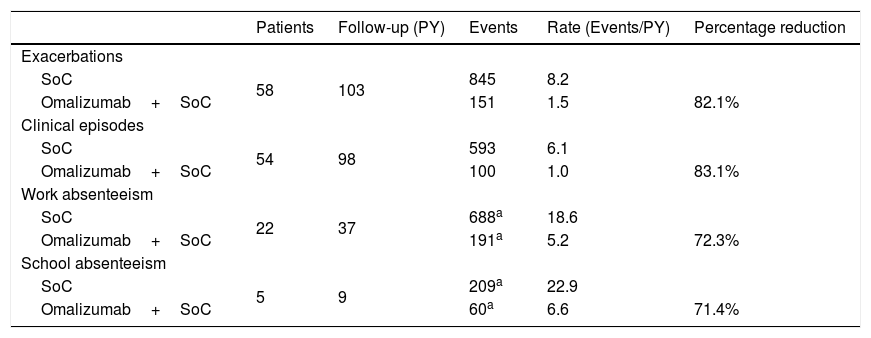

Retrospective and prospective information on exacerbations was available for a total of 58 patients (Table 3). Under omalizumab plus standard of care, 151 exacerbations occurred for a total follow-up of 103 patient-years, leading to a rate of 1.5 exacerbations per patient-year. Continuing the pre-omalizumab pattern of exacerbations, during the same total follow-up, would have led to an estimated 845 exacerbations under standard of care alone, corresponding to a rate of 8.2 exacerbations per patient-year. This implies an 82.1% reduction in the incidence of exacerbations for omalizumab plus standard of care as compared to standard of care alone. Similar results were obtained for the remaining event-related effectiveness outcomes (Table 3).

Estimated effectiveness with omalizumab plus standard of care and standard of care alone for the Portuguese patients in the eXpeRience registry.

| Patients | Follow-up (PY) | Events | Rate (Events/PY) | Percentage reduction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exacerbations | |||||

| SoC | 58 | 103 | 845 | 8.2 | |

| Omalizumab+SoC | 151 | 1.5 | 82.1% | ||

| Clinical episodes | |||||

| SoC | 54 | 98 | 593 | 6.1 | |

| Omalizumab+SoC | 100 | 1.0 | 83.1% | ||

| Work absenteeism | |||||

| SoC | 22 | 37 | 688a | 18.6 | |

| Omalizumab+SoC | 191a | 5.2 | 72.3% | ||

| School absenteeism | |||||

| SoC | 5 | 9 | 209a | 22.9 | |

| Omalizumab+SoC | 60a | 6.6 | 71.4% |

SoC – standard of care; PY – person-years.

For GETE response to therapy, prospective data was available for 58 of the 62 patents (Fig. 2) after a median follow-up of 17 weeks. Considering the previously introduced five-point scale, average GETE response for omalizumab plus standard of care was estimated at 2.3, corresponding to a good-to-moderate response. With the counterfactual average GETE response on standard of care of ‘5-worsening’ for all participants, this implies a 54.1% reduction in GETE-score.

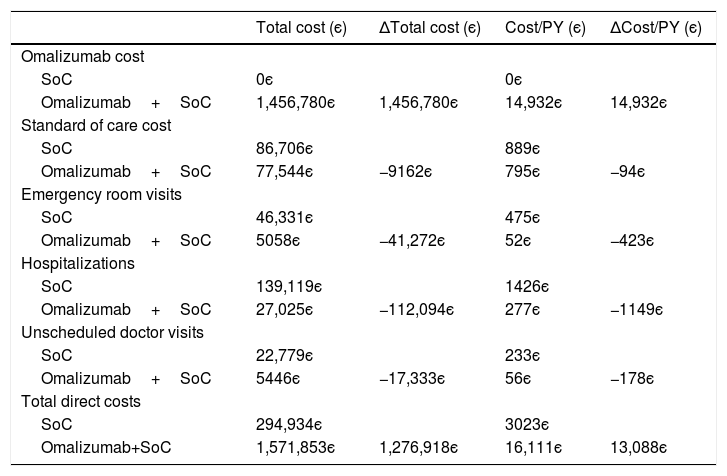

CostsFor 54 Portuguese patients enrolled in the eXpeRience registry (Table 3), sufficient information on clinical episodes was available to estimate the impact of add-on therapy with omalizumab on direct costs. As can be seen from Table 4, over the considered time-horizon average 22 months, an estimated additional annual per-patient cost of 14,932є due to omalizumab therapy is expected to be off-set by a saving of 1844є in the remaining direct costs (85.3% of which due to avoided hospitalizations and emergency room visits). This leads to a net increase of 13,088є in annual per-person direct costs.

Estimated direct costs with omalizumab plus standard of care and standard of care alone for the Portuguese patients in the eXpeRience registry (based on 54 patients for which sufficient information on clinical episodes was available).

| Total cost (є) | ΔTotal cost (є) | Cost/PY (є) | ΔCost/PY (є) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omalizumab cost | ||||

| SoC | 0є | 0є | ||

| Omalizumab+SoC | 1,456,780є | 1,456,780є | 14,932є | 14,932є |

| Standard of care cost | ||||

| SoC | 86,706є | 889є | ||

| Omalizumab+SoC | 77,544є | −9162є | 795є | −94є |

| Emergency room visits | ||||

| SoC | 46,331є | 475є | ||

| Omalizumab+SoC | 5058є | −41,272є | 52є | −423є |

| Hospitalizations | ||||

| SoC | 139,119є | 1426є | ||

| Omalizumab+SoC | 27,025є | −112,094є | 277є | −1149є |

| Unscheduled doctor visits | ||||

| SoC | 22,779є | 233є | ||

| Omalizumab+SoC | 5446є | −17,333є | 56є | −178є |

| Total direct costs | ||||

| SoC | 294,934є | 3023є | ||

| Omalizumab+SoC | 1,571,853є | 1,276,918є | 16,111є | 13,088є |

SoC – standard of care; PY – person-years.

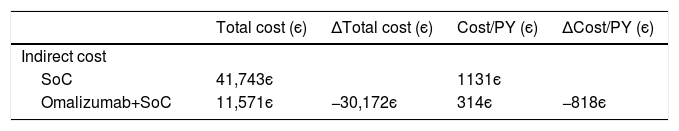

The impact on indirect costs due to the introduction of omalizumab could only be estimated on the basis of 22 patients for whom data on work absenteeism was available (Table 3). Given the 72.3% reduction in missed days of work, for these patients, a reduction in indirect costs of 818є per person-year was estimated (Table 5).

Estimated indirect costs with omalizumab plus standard of care and standard of care alone for the Portuguese patients in the eXpeRience registry (based on 22 patients for which sufficient information on work absenteeism was available).

| Total cost (є) | ΔTotal cost (є) | Cost/PY (є) | ΔCost/PY (є) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect cost | ||||

| SoC | 41,743є | 1131є | ||

| Omalizumab+SoC | 11,571є | −30,172є | 314є | −818є |

SoC – standard of care; PY – person-years.

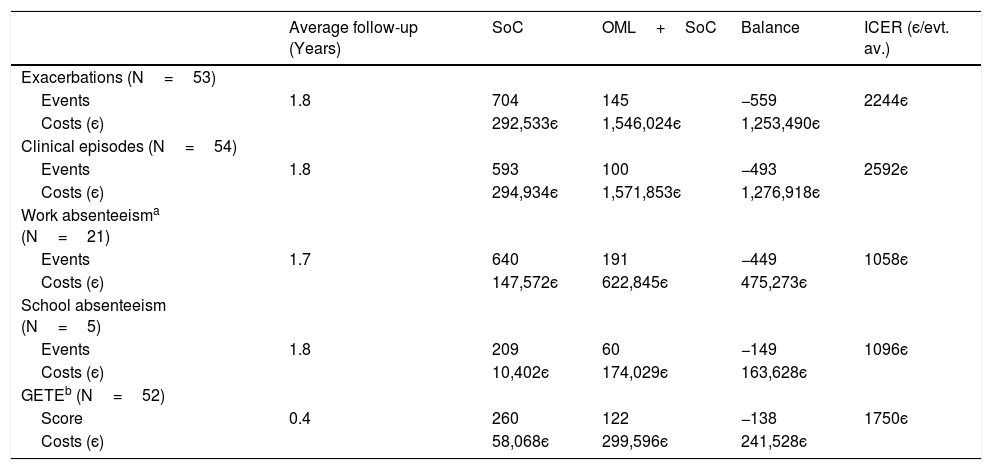

As described earlier, ICERs were estimated only for patients for whom both the effectiveness outcome and a full cost estimation was possible.

Of the 58 patients for whom effectiveness estimates are available in terms of the number of exacerbations (Table 3), 5 patients were not included in the direct cost estimate due to a lack of information about clinical episodes. For the remaining 53 patients, cost-effectiveness results are presented in Table 6. Over an average follow-up of 1.8 years, a total of 559 exacerbations were estimated to have been avoided with omalizumab plus standard of care over standard of care alone. This comes to an estimated increase in total direct costs of 1,253,490є, resulting in an ICER of 2244є per exacerbation avoided.

Estimated incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for omalizumab plus standard of care as compared to standard of care alone for the Portuguese patients in the eXpeRience registry.

| Average follow-up (Years) | SoC | OML+SoC | Balance | ICER (є/evt. av.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exacerbations (N=53) | |||||

| Events | 1.8 | 704 | 145 | −559 | 2244є |

| Costs (є) | 292,533є | 1,546,024є | 1,253,490є | ||

| Clinical episodes (N=54) | |||||

| Events | 1.8 | 593 | 100 | −493 | 2592є |

| Costs (є) | 294,934є | 1,571,853є | 1,276,918є | ||

| Work absenteeisma (N=21) | |||||

| Events | 1.7 | 640 | 191 | −449 | 1058є |

| Costs (є) | 147,572є | 622,845є | 475,273є | ||

| School absenteeism (N=5) | |||||

| Events | 1.8 | 209 | 60 | −149 | 1096є |

| Costs (є) | 10,402є | 174,029є | 163,628є | ||

| GETEb (N=52) | |||||

| Score | 0.4 | 260 | 122 | −138 | 1750є |

| Costs (є) | 58,068є | 299,596є | 241,528є |

OML – omalizumab; SoC – standard of care; evt. av. – event avoided.

With the exception of GETE response to therapy, for the remaining effectiveness outcomes a similar analysis was performed (Table 6), leading to ICERs of 2592є per clinical episode avoided (54 patients), 1058є per day of work absenteeism avoided (21 patients), and 1096є per day of school absenteeism avoided (5 patients). For work absenteeism, the only outcome for which indirect costs were considered, the increase in total costs of 475,273є is the result of an increase of 502,538є in total direct costs, off-set by a decrease in total indirect costs of 27,265є.

For GETE response to therapy, with costs calculated only up to the corresponding response evaluation visit, over an average follow-up of 19 weeks (0.4 years), treating patients with omalizumab plus standard of care as compared to standard of care alone is estimated to lead to an ICER of 1750є per unit decrease in GETE classification.

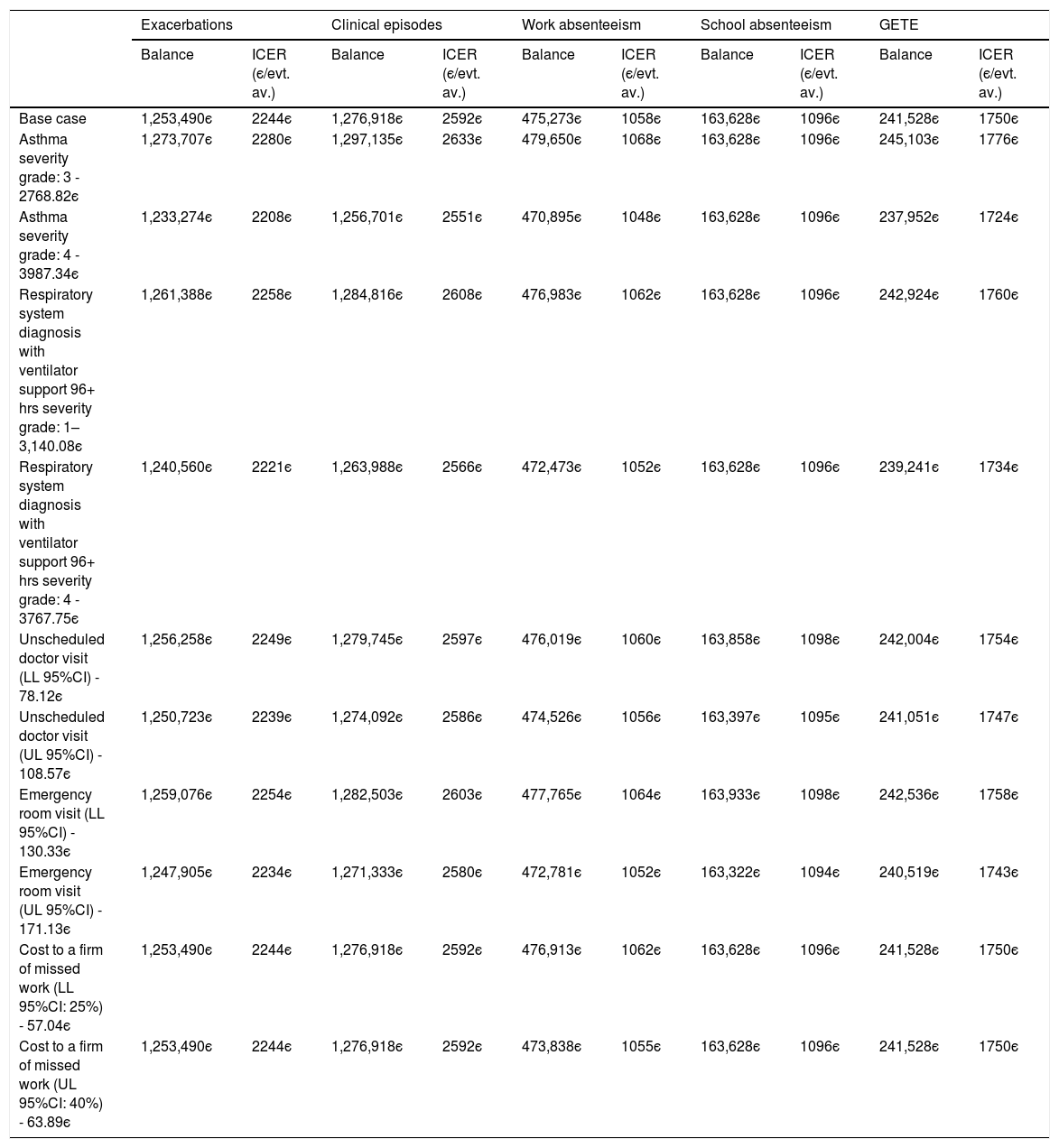

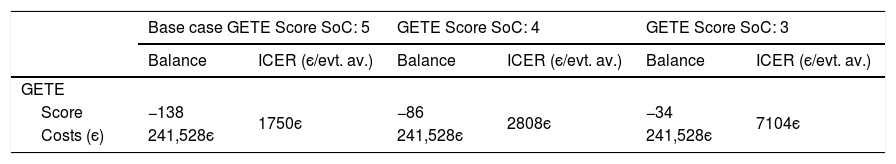

Sensitivity analysisThe univariate sensitivity analysis shows that considering the different costs of hospitalization, the ICER varies between 2208є and 2258є per exacerbation avoided. Changing the cost of work absenteeism (cost per absent day) according to the 95% confidence interval limits, the ICER per avoided day of work absenteeism varies between 1055є and 1062є (Table 7). Finally, considering a GETE response rated with 3 – “moderate” and 4 – “poor” instead of “5-worsening” for all participants for the counterfactual standard of care generates ICER values of 7104є and 2808є per unit decrease in GETE classification, respectively (Table 8).

Univariate sensitivity analysis at costs parameters.

| Exacerbations | Clinical episodes | Work absenteeism | School absenteeism | GETE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balance | ICER (є/evt. av.) | Balance | ICER (є/evt. av.) | Balance | ICER (є/evt. av.) | Balance | ICER (є/evt. av.) | Balance | ICER (є/evt. av.) | |

| Base case | 1,253,490є | 2244є | 1,276,918є | 2592є | 475,273є | 1058є | 163,628є | 1096є | 241,528є | 1750є |

| Asthma severity grade: 3 - 2768.82є | 1,273,707є | 2280є | 1,297,135є | 2633є | 479,650є | 1068є | 163,628є | 1096є | 245,103є | 1776є |

| Asthma severity grade: 4 - 3987.34є | 1,233,274є | 2208є | 1,256,701є | 2551є | 470,895є | 1048є | 163,628є | 1096є | 237,952є | 1724є |

| Respiratory system diagnosis with ventilator support 96+ hrs severity grade: 1–3,140.08є | 1,261,388є | 2258є | 1,284,816є | 2608є | 476,983є | 1062є | 163,628є | 1096є | 242,924є | 1760є |

| Respiratory system diagnosis with ventilator support 96+ hrs severity grade: 4 - 3767.75є | 1,240,560є | 2221є | 1,263,988є | 2566є | 472,473є | 1052є | 163,628є | 1096є | 239,241є | 1734є |

| Unscheduled doctor visit (LL 95%CI) - 78.12є | 1,256,258є | 2249є | 1,279,745є | 2597є | 476,019є | 1060є | 163,858є | 1098є | 242,004є | 1754є |

| Unscheduled doctor visit (UL 95%CI) - 108.57є | 1,250,723є | 2239є | 1,274,092є | 2586є | 474,526є | 1056є | 163,397є | 1095є | 241,051є | 1747є |

| Emergency room visit (LL 95%CI) - 130.33є | 1,259,076є | 2254є | 1,282,503є | 2603є | 477,765є | 1064є | 163,933є | 1098є | 242,536є | 1758є |

| Emergency room visit (UL 95%CI) - 171.13є | 1,247,905є | 2234є | 1,271,333є | 2580є | 472,781є | 1052є | 163,322є | 1094є | 240,519є | 1743є |

| Cost to a firm of missed work (LL 95%CI: 25%) - 57.04є | 1,253,490є | 2244є | 1,276,918є | 2592є | 476,913є | 1062є | 163,628є | 1096є | 241,528є | 1750є |

| Cost to a firm of missed work (UL 95%CI: 40%) - 63.89є | 1,253,490є | 2244є | 1,276,918є | 2592є | 473,838є | 1055є | 163,628є | 1096є | 241,528є | 1750є |

SoC – Standard of care; evt. av. – event avoided.

Univariate sensitivity analysis for GETE response.

| Base case GETE Score SoC: 5 | GETE Score SoC: 4 | GETE Score SoC: 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balance | ICER (є/evt. av.) | Balance | ICER (є/evt. av.) | Balance | ICER (є/evt. av.) | |

| GETE | ||||||

| Score | −138 | 1750є | −86 | 2808є | −34 | 7104є |

| Costs (є) | 241,528є | 241,528є | 241,528є | |||

SoC – Standard of care; evt. av. – event avoided; GETE scale: 3 – “moderate”, 4 – “poor” and 5 – “worsening”.

Asthma is a chronic disease representing a major public health problem with evident socio-economic consequences in most developed countries.4–6 The profile of complications and the intense need for differentiated health care in patients with severe persistent asthma results in costs three to four times higher than those of patients with less serious asthma.5

Clinical trials and observational studies have further demonstrated that patients treated with omalizumab plus standard of care have a reduction of asthma exacerbations, fewer clinical episodes and present less days of work and school absenteeism than patients treated with standard of care alone.17–21 Savings in both direct and indirect costs, however, are likely to be off-set by an increase in drug costs due to the add-on nature of omalizumab therapy.

The present health economic evaluation considers as primary source for effectiveness data and resource consumption associated with the management of severe allergic asthma with omalizumab, data from the 62 Portuguese participants of the eXpeRience registry.20 In health economic evaluation, the inclusion of real-world data has the potential to provide policy makers with a more relevant and realistic picture of costs and effects in daily practice than an RCT based evaluation.31

Our results are comparable to those presented in other cost-effectiveness studies on omalizumab therapy for severe asthma in real clinical practice.32–34 In a study based on 79 Spanish patients receiving omalizumab for 10 months, a reduction of 7.75 in number of exacerbations with emergency room visits in 10 months was found.33 Another Spanish study, based on 71 patients receiving omalizumab for 12 months, found a reduction of 7.72 in annual exacerbations rate, including a reduction of 4.17 in exacerbations by year leading to either an emergency room visit or hospitalization.34 This study further estimated an 11,483є increase in annual direct costs, leading to an ICER of 1487є per avoided exacerbation. A study of 23 Italian patients receiving omalizumab over an average follow-up of 10 months showed an annual reduction of 6.27 clinical episodes and 17.61 days of inactivity.32

In the eXpeRience registry, prior to omalizumab treatment, an average rate of 4.9 exacerbations per year was observed. During the omalizumab treatment phase of the study, after 12 months, this rate decreased by 80% to an average rate of 1 exacerbation per year. For the Portuguese subgroup of eXpeRience patients, prior to omalizumab treatment, an average rate of 8.2 exacerbations per year was observed, whereas after 12 months of omalizumab treatment, 1.5 exacerbations per year were observed, close to the 12-month rate of the overall eXpeRience registry population, despite a higher baseline exacerbation rate. Besides potential differences in treatment optimization and asthma control at registry entry between the different countries included in the eXpeRience registry, the higher number of exacerbations prior to omalizumab treatment in the Portuguese subgroup of the registry might be explained, in part, by the geographical location, with a long Atlantic coast and high levels of humidity, influencing the severity of the disease.35–37

Despite the advantages of the inclusion of Portuguese real-world data from the eXpeRience registry, our study is not without limitations. First, due to the lack of a comparator arm in the eXpeRience registry, a standard of care arm had to be simulated based on retrospective data on exacerbations, healthcare utilization, and absenteeism. Second, with an average follow-up of only 22 months, it was not possible to consider a lifetime time horizon, typically used when considering the health economic evaluation of therapies for chronic diseases. Third, since the Portuguese participants in the eXpeRience registry only responded to the mini-AQLQ questionnaire,38 for which no conversion algorithm to EQ-5D utilities is available, it was not possible to incorporate health outcomes by means of the quality of life component. Fourth, indirect costs are based on limited data about the number of missed days of work and could not be stratified according to the type of job of patients, due to a lack of detailed information. Nevertheless, given the implications of the disease on work absenteeism, the analysis was performed. Fifth, as in the current analysis the results for the omalizumab treatment arm are “as observed” in the eXpeRience registry, no probabilistic sensitivity analysis can be performed on the outcomes taken directly from the registry. Last, given the pragmatic nature of the analysis, data imputation methods for retrospective missing data (e.g.: Mutiple Imputation by Chained Equations39 and others40–42 were not considered.

In conclusion, the evidence produced in this study demonstrates that adding omalizumab to the treatment of patients with uncontrolled severe persistent asthma reduces the number of exacerbations, improving overall treatment effectiveness at an acceptable cost from a societal perspective.

Conflict of interestsAA: Declares collaborating and receiving fees from Astra-Zeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Laboratórios TEVA, Mundipharma, and Roche, through either participation in advisory board or consultancy meetings or congress symposia.

MPB: Speaker and Chair of symposia by invitation from Novartis Pharma AG. Scientific adviser of Diater.

BV: No conflict of interest.

SR: No conflict of interest.

JF: No conflict of interest.

Declaration of financial/other relationshipsCo-authors SR, BV, and JF are employees of EXIGO, a consulting company that provides services to several pharmaceutical companies, including Novartis Farma SA and Novartis Pharma AG, and received funding to complete this analysis.

Supported by funding from Novartis Pharma AG. The funding organization provided feedback on the design of the model and the inputs/sources used in the model. The funding organization also reviewed the manuscript.