Publication of scientific research is important for many reasons. You may be forced to publish because you are competing for funding, because you need to improve your curricula and get a better position or simply because you are selfish and want to enjoy yourself! Whatever the reasons, the publication process has a positive impact on your own work, often suggesting new avenues which otherwise you would not have explored in your research. However, preparing a good report is not an easy task.

It is often the case that people who are good with numbers are not good at writing and vice versa. If your friend is good at both, there you are with a potential professor! A good coach will tell you to understand your own weaknesses and about the need for cooperation with other researchers. Starting to write is not only difficult for junior researchers owing to their lack of experience and skills at the beginning of their career, but it is also a challenge for good and experienced writers. An unsystematic search we made on PubMed about “writing a scientific paper” produced about 325 reports, most of them were excellent! So, considering the number of available publications on the web, from editorial boards or post graduation syllabus, why do we need yet another paper on scientific writing? Well… because our friends asked us! – and that may be another reason for writing!

But dear readers relax! This paper isn’t an exercise in friendship. The following pages contain some of the best hidden secrets of manuscript preparation and will provide you with an accurate guide to successful writing!

The emphasis will be on the structure and style of the sections common to all research reports but we will also briefly cover some of the most frequently made mistakes and suggest strategies to avoid them. Fasten your seat belts and enjoy the reading!

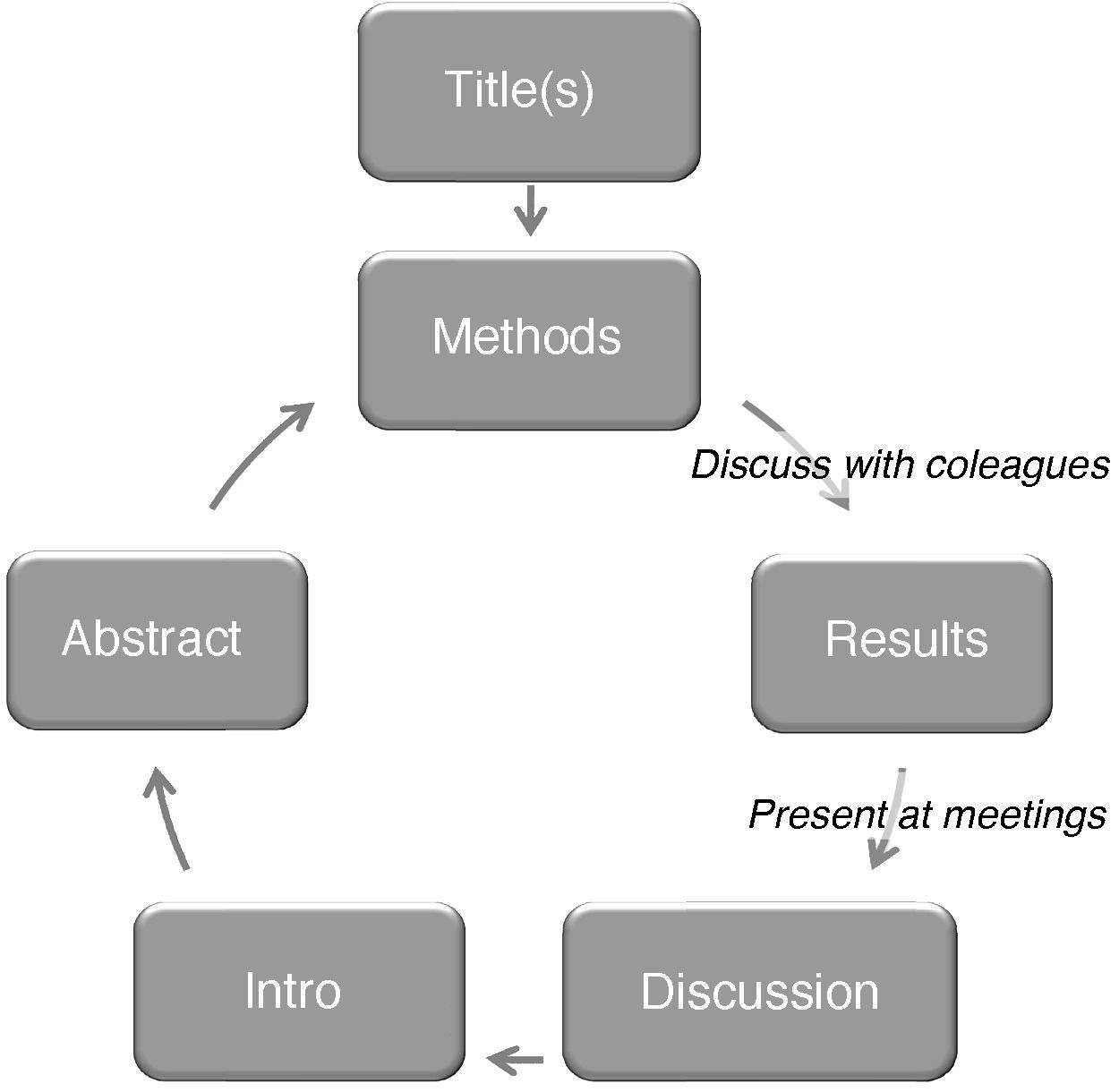

Start with what you feel is the easiest bit for you!Do not start from A and end up with Z, it does not work. Start where you feel most comfortable! (Figure 1). This is usually Materials and Methods (you have done the work, so you should know how you did it!). Proceed then to Results, presenting the essential observations in numbers, in one to three Tables. After all, the actual numbers do matter and how you have classified them and treated them in terms of statistics. Tables and numbers are often lengthy and boring, so try to cut down and leave out the less meaningful numbers even though you may have a personal love affair with them. Figures are the best way to convey the message to the readers at a glance! They are less accurate but give the readers something to steal from your paper – 99 out of 100 steal the Figure. So, plan to display your intriguing results in one or two figures so as to seduce your fans and smuggle your work into their Power Point presentations. Around the methods and results you then create your bla bla bla story. Make the intro quite short; explain why you did the study in the first place, and mention those who have already done a much better job. Then comes a more lengthy discussion where you try to put your findings into perspective. Do not start from the ancient Egyptians, history is interesting but not THAT interesting. Reviewers hate long discussions - 1 page is not enough in a full paper, but 4 pages is too much, 2 and 1/2 would be OK for New England Journal of Medicine (and should also be so for your peers!).

Make it easyIt is recommended that experimental articles should be divided into the following sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion1. Using this so-called “IMRAD” structure format allows a reading at several different levels. For instances, you can take a snapshot of the study by just reading the last paragraph of the discussion, skipping the rest and rapidly getting what you need. For those wanting to go deeper, electronic formats have created opportunities for adding details or whole sections under the online depository. There are exceptions from the IMRAD structure such as case reports, reviews, and editorial reports. The take home point here is the structure you follow will ensure that different levels of reading are possible and will quickly and easily provide the reader with the key results and conclusions.

Hook the reader!The purpose of the “Introduction” is to establish the context of our work. This can usually be accomplished in three to four paragraphs. First, what you were studying and why it was important; secondly, what we knew about it and what the current gaps are; finally, what your brilliant idea of solving the problem was. Organize this section so that it narrows from the more general aspects towards the more specific topical information that provides context. Finally arrive at your statement of rationale. Don’t be exhaustive in the introductory review of the literature and give only pertinent references! Present the logical relationships among previous studies and avoid enumerating a list of unrelated citations. Then, the purpose of your work should naturally follow in the form of hypothesis. End with a sentence explaining the aim of your study. The focal point of this section is to hook the reader!

Be methodical!Although the “material and methods” section is the most important part of your work it has the tendency to be squeezed in published reports. This happens because of space constraints and also because readers are usually not particularly interested in details. Even so this is the “playmaker” section of your paper. Organize it that the reader will understand the logical flow of the study. You may include separate descriptions of the participants and study design and procedures. These are subtitled and may be augmented by further sections, if needed.

Do not forget: i) to clearly state the eligibility and exclusion criteria of participants and a description of the source population. In clinical trials, the table 1, patient caractheristics, is crucial. The results are only valid in them; ii) to identify the methods, apparatus (give the manufacturer's name and address in parentheses), and procedures giving enough information to allow another researcher to repeat it; iii) in clinical trials, to characterize precisely the intervention procedures and, in review manuscripts, to include methods used for locating, selecting, extracting, and synthesizing data; iv) finally, state how the data was summarized and analyzed, indicating what types of descriptive statistics and statistical analysis were used to determine significance. Only new or substantially modified methods should be described and reasons for using them given; you can also explain methods limitations/constraints in this section. Established methods should be briefly described with the appropriated citation.

All work involving studies with human subjects is expected to have received approval from local ethical committees and the regulatory authority. This is such an important aspect of this section that it should be brought into the first or last paragraph of this section.

Do not forget methods are the most important part of your work, they dictate your results and conclusions and the overall strength of your paper. The focus here is to explain – in clear and simple language – how you carried out your study. If you are asked to act as a reviewer for a submitted article, read first the title, then material and methods. If they are rubbish do not waste any more time.

Your study in one figure!The results section is easy to write: just present your key results without any form of interpretation! Often the results section is not more than one page (plus the tables and figures). Results should flow logically and appear in an orderly sequence starting with the main result related to the aim of your research. The text should lead the reader through your key observations including references to one to three tables, and optionally one or two figures. Make them highlight your key findings to give the Eureka! experience at one glance. Do not draw conclusions in the results section - reserve data interpretation for the discussion.

Every paper contains errors!Remember there are no perfect studies! The Ancient Chinese once did a perfect piece of work, but it was so perfect that they decided to conceal two deliberate mistakes in it (no man does a perfect job!). One of the most important aspects of the discussion is to acknowledge study limitations, particularly because the reviewer is going to find them anyway! Study weaknesses would be such as those related to sample size not being powerful enough or methods not being the most appropriate to test the hypothesis. Justify your methodological approach, especially if it deviates from the norm. You should not hide the strengths of your approach and paper altogether, but there is one thing to avoid. Do not state that your paper is the first one to show this or that. You can be sure that you will be shot down!

The classical structure of the discussion will include one paragraph for each of the following in this order: i) interpretation of the main findings results, ii) limitations and iii) strengths of your study, iv) relation to the findings of previous studies, v) explanation and generalizability of the observations, vi) clinical implications, and vii) conclusion. Finish your paper with a very brief descriptive paragraph, of 2 or 3 sentences, about the clinical implications (if your paper includes a clinical message). Summarize the diagnostic, therapeutic, or management implications of your research. These sentences should succinctly affirm why the article is important and what significance it has for the clinician. This paragraph may also appear in the cover letter of the manuscript to the editor.

You should not forget that the function of the Discussion is to tell the reader what your results add to what was already known on the topic! It should not be a repetition of the introduction, methods or results. Instead, draw conclusions, discuss implications and limitations, and relate with other observations from other studies summarizing the evidence for each conclusion. It is bad habit to end every paper by stating “further studies are needed”. Sure, science is never ending story, but state what we specifically need to do to understand the problem better.

Treat the abstract as a mini-paper!Even though it is the first section of your paper, it's much easier if you write the abstract at the end. Just take key sentences from each section and put them in a sequence which summarizes the paper. Then polish and revise making it consistent and clear – a short story of its own.

The abstract should not contain lengthy background information, references, abbreviations or any sort of illustration, figure, or table. State the purpose very clearly in the first or second sentence, describe the study design and methodology without going into excessive detail, express main findings that answer our research question and conclude by emphasizing new and important aspects of your results. Remember the abstract should stand on its own and be as succinct as possible! Many readers only read the two-three-line conclusions! Concentrate your intelligence on those lines.

The crystal effect: the more you develop the paper, the shorter it becomes!You have selected your first and second choice journals taking into consideration, relevance to your study, quality suitable to your data, and maybe impact factor. Finally you have the Journal “instructions to authors” and have agreed with your co-authors on deadlines. Somehow this is the moment, if you have not already done so, to share the manuscript revision with your co-authors and start the in-house revision marathon. Your co-authors will be those who make substantial contributions to conception and study design or, data acquisition or, data analysis and interpretation, and drafting or revising the paper. They should read and approve the final version of the manuscript. One truth: “If you do not have time, the story is going to be long and exhausting to the reader”. The more you develop the paper, the shorter it becomes!

Sum up in 6 wordsThe title should concisely describe the contents of the paper. Often there is a working title but it changes along the road and it might be the last thing to be decided before submission. Use descriptive words that are strongly associated with the content of your paper. Remember your paper will also be found by electronic search engines looking for keywords in the title.

Some journals like to have the result already in the title; some others hate that and just want you to give the approach used such as double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial comparing this and that... We feel that more informative titles are better that the bla bla titles, but of course some caution is needed.

Kiss!One paper, one message! Do not put too much data in one article. Focus, focus and focus…Decide what your message is and build up a story around it. If you have a lot of data do another article or even a third one! Reviews and metha-analyses are another story, but even there keep it short and simple!

You may also consider submitting you work as a short report or as a letter to the Editor! They are usually acknowledged in PubMed, ISI, etc. and do not worry: your masterpiece can fit into 600 words, no problem!

Pay attention to detail!Make sure your presentation is clear and concise, ask an expert to review spelling and grammar, confirm figures and tables are labeled properly and references are accurate.

Check you have an appropriate paragraph structure. Each paragraph should stand on its own. The first sentence is the topic or message you want to convey; followed by two or three sentences, developing it; and closely linking with the next paragraph/topic. Ideally you should create in the reader the need for the following bit. A very practical rule is to identify and highlight sentences that are essential; if they appear in the beginning, great; if they appear in the middle, move them; several highlights together, rearrange the text.

Perform a fluency test, reading you paper from start to finish. There should be no areas of concern, incorrect statements or awkward sentences. When you read your paper from start to finish, do you really understand it yourself? If there is the faintest doubt, you can be sure your case will be lost with the majority of other readers as well. Use short and full sentences. Use periods much more than commas. If your text proceeds like a snake, it becomes toxic and will get kicked off.

Do think carefully about the references, because they will have a direct relation to the reviewers who are likely to be picked by the editor. Old gurus look first at the references; if their names are not there, they do not read on - must be a bad paper! The writers of this article feel that the reviewer process should be, in fact, double-blind. The author names or affiliations should not be open to the reviewers. Even scientists are human, they like to make friends and keep them. Big boys like big boys, some also Big Girls. If a paper comes from an obscure Island somewhere in the South-Pacific, and the authors are not known, end of story for the Big Boy. But if the paper comes from Oxford or Harvard, no matter how trivial it may be, it gets full attention and the threshold for acceptance is much lower. We wish there were fair-play.

Do not forget acknowledgements, it does not hurt, or cost anything, to thank people and your funders, but forgetting them is an unnecessary risk for your future career!

Have a beer!While revising the manuscript and incorporating suggestions from your co-authors carefully prepare the covering letter to the editor which should make clear what the key message of your research is as well as the clinical implications.

Whatever the outcome prepare for a beer with friends! In the event of rejection, update your work with reviewers’ comments and after a beer resubmit to another journal. Be relax. Strange things happen. Once we submitted a paper to a modest Journal, followed by rejection and hard criticisms. Then we submitted it to a higher impact Journal, after some improvements. And guess what? Again rejected, but the criticism was fair. All right, some fine-tuning and off to a third Journal and this time to a really high-impact one. Jackpot! So, life is not fair and objective.

At the end of the long journey – on average four years after starting the study – your paper is accepted. Have a fiesta for 24hours! A good treatment for a hangover is to plunge into the next paper. Whatever the outcome, reflect on what you have learned and how you can improve yourself. Writing is an addiction for novelists, but they have one advantage over you. They do not allow the facts to ruin a good story. Your writing is on the more boring side, but there you are, just make a small twist of the words and do not allow the good story to ruin your facts. But it is still a story, and scientists love them as much as normal people. Science is fun; you never know what is ahead when you set off.

Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals: writing and editing for biomedical publication updated October 2004. Mymensingh Med J. 2005 Jan;14(1):95-119

- Home

- All contents

- Publish your article

- About the journal

- Metrics

- Open access