Lung cancer staging has recently evolved to include endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) for nodal assessment.

AimEvaluate the performance and safety of EBUS-TBNA as a key component of a staging algorithm for non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) and as a single investigation technique for diagnosis and staging of NSCLC.

MethodsPatients undergoing EBUS-TBNA for NSCLC staging at our institution between April 1, 2010 and December 31, 2014 were consecutively included with prospective data collection. EBUS-TBNA was performed under general anesthesia through a rigid scope.

ResultsA total of 122 patients, 84.4% males, mean age 64.2 years. Histological type: 78 (63.9%) adenocarcinoma, 33 (27.0%) squamous cell carcinoma, 11 (8.9%) undifferentiated/other NSCLC. A total of 435 lymph node stations were punctured. Median number of nodes per patient was 4. EBUS-TBNA nodal staging: 63 (51.6%) N0; 8 (6.5%) N1; 34 (27.9%) N2, and 17 (13.9%) N3. EBUS-TBNA was the primary diagnostic procedure in 27 (22.1%) patients. EBUS-TBNA NSCLC staging had a sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and diagnostic accuracy rate of 83.3, 100, 100, 86.1, and 91.8%, respectively. No complications were attributable to the procedure.

ConclusionA comprehensive lung cancer staging strategy that includes EBUS-TBNA seems to be safe and effective. Our EBUS-TBNA performance and safety in this particular setting was in line with previously published reports. Additionally, our study showed that, in selected patients, lung cancer diagnosis and staging are achievable with a single endoscopic technique.

In spite of all advances in surgical treatment and multimodality treatment, lung cancer is still the most common cause of cancer death across the world.1 In Portugal, lung cancer is the fourth most common malignancy, with a crude incidence of 30.6 per 100,000 inhabitants, and the second highest cause of malignancy disease death.2 Accurate staging is important in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who are fit for surgery and have no evidence of extrathoracic disease, because mediastinal lymph nodes disease status is an indicator for treatment with curative intent.3

Several invasive and non-invasive techniques are available to support lung cancer staging. Imaging methods, such as computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET), indicate size and metabolic activity of mediastinal nodes, respectively, but the lack of specificity is an important pitfall.4 Therefore, tissue confirmation of suspected malignant lymphadenopathy is required, especially before surgical resection. Surgical staging by mediastinoscopy presents a high sensitivity and specificity and was for many years the gold standard modality for this purpose.5,6 However, it is a surgical procedure that requires general anesthesia and clinical admission.

Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) is a newer technique that allows minimally invasive sampling of intrathoracic lymph nodes adjacent to the bronchial tree and it is gradually replacing mediastinoscopy as NSCLC staging gold standard.5 In recent guidelines,3 lung cancer staging has evolved to include EBUS-TBNA for nodal assessment.

The aim of our work was to evaluate our EBUS-TBNA performance and safety as a key component of a staging algorithm for NSCLC and as a single investigation technique for diagnosis and staging of NSCLC.

MethodsPatientsFrom April 1, 2010 and December 31, 2014, all consecutive patients referred for EBUS-TBNA with the purpose of NSCLC staging at our institution were prospectively included in our study. Chest CT was mandatory before the procedure (PET or PET-CT was dependent upon referring physician decision). Primary exclusion criteria were, significant concurrent malignant disease or any condition or concurrent medicine that contraindicated EBUS-TBNA. Secondary exclusion criteria were added to ensure maximum homogeneity on our EBUS staging performance evaluation: patients that received induction chemotherapy, that were lost to follow up, or that had a surgery related complication that precluded a correct mediastinal surgical staging were excluded from this latter analysis.

The 7th edition of the TNM staging system in lung cancer was used throughout.

ProceduresEBUS-TBNA was performed under general anesthesia with flexible ultrasound bronchoscope (BF-UC180F, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) through a rigid scope in an outpatient setting. A systematic examination of all mediastinal and hilar lymph node stations was conducted. N3 nodes were first punctured, followed by N2 and lastly ipsilateral hilar N1 nodes, if appropriate. Transbronchial aspiration was performed through a dedicated 22-gauge or 21-gauge needle (NA-201SX-4021/2, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and with application of negative pressure. At least two needle passes per station were carried out. Additional punctures were performed when rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) or the macroscopic appearance of the acquired material was not satisfactory. The aspirated material was smeared onto glass slides. Smears were fixed in alcohol and immediately stained with hematoxylin/eosin staining protocol for ROSE by a cytopathologist. Specimens were categorized as positive (tumor cells), negative (lymphoid but no tumor cells), or inconclusive (poor cellularity).

Statistical methodsA descriptive analysis was carried out in which categorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies and continuous variables as means and standard deviation.

For statistical purposes in our EBUS staging performance evaluation, it was assumed that a positive EBUS-TBNA for N2/N3 disease (with or without surgical-pathologic confirmation) was a true positive. A N0/N1 staging obtained by EBUS-TBNA and confirmed by subsequent methods (invasive or 6 month clinical and radiological follow-up) was considered a true negative. A negative EBUS-TBNA result that was later confirmed to be positive for malignancy by other invasive methods in the same anatomical location or by disease progression on clinical follow up was a false-negative. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and diagnostic accuracy rate were calculated using the standard definitions.

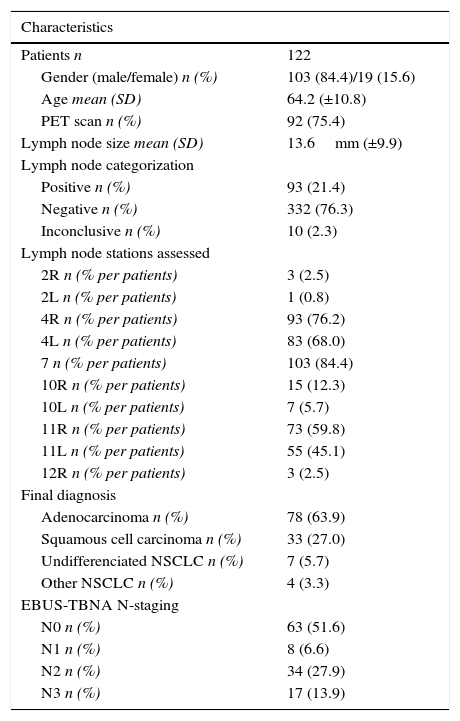

ResultsOut of a total of 437 patients submitted to EBUS at our institution, 122 patients were included in our study (mean age 64.2±10.8 years; 84.4% males). Patient characteristics, lymph node size, categorization and stations assessed, final diagnosis, and N staging are presented in Table 1. A total of 435 nodes were punctured (ultrasonographic mean size 13.6±9.9mm, range 4–86mm), with a median of two needle passes for each site and four nodes per patient. The three most assessed node stations were station 7 (n=103; 23.7% of patients), station 4R (n=93; 21.3% of patients), and station 4L (n=83; 19.0% of patients). PET scan was available in 75.4% of patients and ROSE in 97% of the procedures. Patients were staged by EBUS-TBNA as follows: 63 (51.6%) N0; 8 (6.6%) N1; 34 (27.9%) N2, and 17 (13.9%) N3. Final diagnosis was divided by histological type in 78 (63.9%) adenocarcinoma, 33 (27.0%) squamous cell carcinoma, 7 (5.7%) undifferentiated NSCLC, 4 (3.3%) other NSCLC. EBUS-TBNA procedure was uneventful and there were no complications in any of the patients.

Patient characteristics, lymph node size, categorization and stations assessed, final diagnosis, and N staging.

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Patients n | 122 |

| Gender (male/female) n (%) | 103 (84.4)/19 (15.6) |

| Age mean (SD) | 64.2 (±10.8) |

| PET scan n (%) | 92 (75.4) |

| Lymph node size mean (SD) | 13.6mm (±9.9) |

| Lymph node categorization | |

| Positive n (%) | 93 (21.4) |

| Negative n (%) | 332 (76.3) |

| Inconclusive n (%) | 10 (2.3) |

| Lymph node stations assessed | |

| 2R n (% per patients) | 3 (2.5) |

| 2L n (% per patients) | 1 (0.8) |

| 4R n (% per patients) | 93 (76.2) |

| 4L n (% per patients) | 83 (68.0) |

| 7 n (% per patients) | 103 (84.4) |

| 10R n (% per patients) | 15 (12.3) |

| 10L n (% per patients) | 7 (5.7) |

| 11R n (% per patients) | 73 (59.8) |

| 11L n (% per patients) | 55 (45.1) |

| 12R n (% per patients) | 3 (2.5) |

| Final diagnosis | |

| Adenocarcinoma n (%) | 78 (63.9) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma n (%) | 33 (27.0) |

| Undifferenciated NSCLC n (%) | 7 (5.7) |

| Other NSCLC n (%) | 4 (3.3) |

| EBUS-TBNA N-staging | |

| N0 n (%) | 63 (51.6) |

| N1 n (%) | 8 (6.6) |

| N2 n (%) | 34 (27.9) |

| N3 n (%) | 17 (13.9) |

Between all patients submitted to EBUS-TBNA with the purpose of primary diagnosis and staging in a single procedure (n=39; 32.0%), primary diagnosis was achieved in 69.2% (n=27) of them. Final diagnosis of these 27 patients was divided by histological type in 23 (85.2%) adenocarcinoma and 4 (14.8%) squamous cell carcinoma.

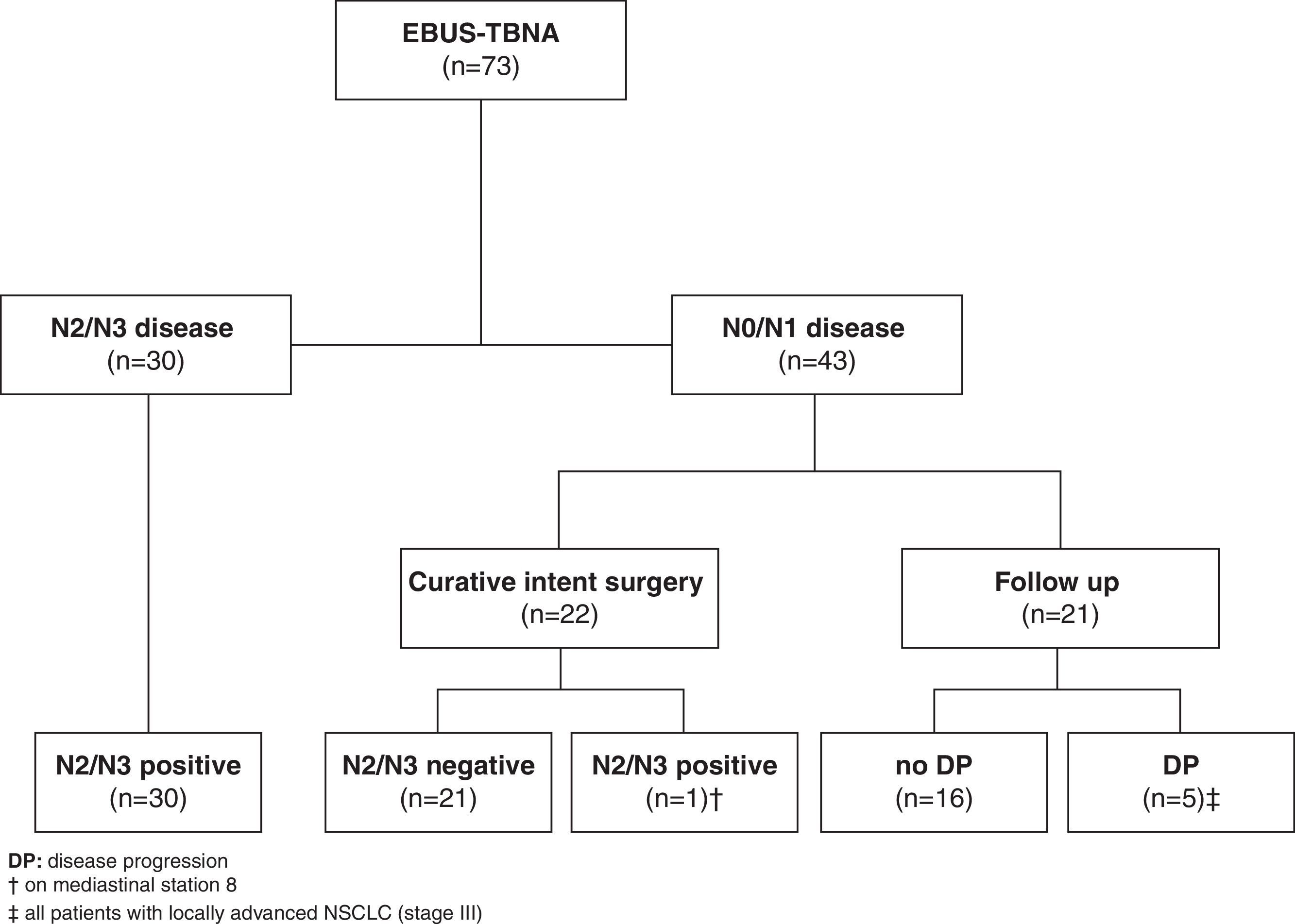

A total of 49 patients were not included in our EBUS staging performance evaluation (38 patients were lost to follow up as they were referred from other institutions, 2 patients had a surgical related complication, and 9 patients received induction chemotherapy). From this remaining group of patients (n=73), EBUS-TBNA demonstrated N2 disease in 21 and N3 disease in 9 patients (a total of 30 (41.1%) patients). The determination of N2/N3 disease was based on malignant cytological results at EBUS-TBNA and all these patients were recorded as true positive.

Forty-three patients with suspected malignant lymphadenopathy had N0/N1 disease by EBUS-TBNA. Out of these, 22 patients underwent curative intent surgery with complete thoracic lymphadenectomy (14 patients had been previously submitted to mediastinoscopy, all confirming EBUS-TBNA previous findings) that confirmed N0/N1 disease in all but one patient, who had N2 disease unreachable by EBUS or mediastinoscopy (station 8). The remaining twenty-one patients were not eligible for curative intent surgery (due to patient's comorbidities or to non-surgical locoregional disease) and had at least 6 months clinical follow-up following multidisciplinary determined treatment approach. Five patients demonstrated clinical or radiologic progression in this follow-up period and were recorded as false negative (Fig. 1).

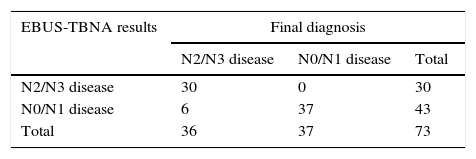

The comparison of EBUS-TBNA results with the final staging obtained by surgical staging or clinical follow-up is shown in Table 2. In our study population, EBUS-TBNA performance in the correct prediction of lymph node stage, including areas unreachable by EBUS had a sensitivity of 83.3%, specificity of 100%, positive predictive value of 100%, negative predictive value of 86.1%, and diagnostic accuracy rate of 91.8%.

Comparison of EBUS-TBNA results with the final diagnoses for prediction of lymph node stage.

| EBUS-TBNA results | Final diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N2/N3 disease | N0/N1 disease | Total | |

| N2/N3 disease | 30 | 0 | 30 |

| N0/N1 disease | 6 | 37 | 43 |

| Total | 36 | 37 | 73 |

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and diagnostic accuracy rate was 83.3, 100, 100, 86.1, and 91.8%, respectively.

Accurate staging is a key factor in the assessment of NSCLC patients, not only as a prognosis definer but also in the decision process of the most suitable treatment plan for both surgical and nonsurgical patients. Therefore, a reliable preoperative assessment of lymph node involvement has a crucial effect on prognosis and therapy. Our results confirm that EBUS-TBNA is a safe and effective assessment method of mediastinal lymph nodes in patients with NSCLC, and that it should play a central role as a part of a comprehensive lung cancer staging strategy.

Additionally, in around 20% of our study population, EBUS-TBNA was the primary diagnostic procedure, reinforcing the point that in selected cases lung cancer diagnosis and staging is achievable with a single endoscopic technique. A recent randomized controlled trial7 showed that EBUS-TBNA, used as initial investigation for patients with suspected lung cancer reduces the time to treatment decision at no additional cost, when compared with conventional diagnosis and staging techniques.

EBUS-TBNA performance for mediastinal staging of NSCLC patients has been extensively described and our results are consistent with previously published reports, with several systematic reviews and meta-analyses reporting the yield of nodal staging for NSCLC by EBUS-TBNA to have a pooled sensitivity of 88–93% and a pooled specificity of 100%.5 EBUS-TBNA (alone or combined with EUS-FNA) diagnostic yield was proved to be at least similar to that of mediastinoscopy,5,7–10 suggesting that mediastinoscopy is rarely needed for the preoperative staging of NSCLC in clinical practice when EBUS-TBNA is available.5,7 Our study results reinforce this knowledge, because mediastinoscopy was unable to detect any false negative lymph nodes in the 14 EBUS-TBNA negative patients that were concomitantly submitted to mediastinoscopy. In fact, these results allowed a change in our center NSCLC staging methodology, with mediastinoscopy performance in EBUS staged N0/N1 patients being dropped from our clinical practice.

Despite being in line with previous studies, our sensitivity rate was slightly affected by the number of false negative cases, especially among patients with non-surgical criteria and on clinical follow up. All these latter five patients had a clinical staging compatible with locoregional disease (stage III), which negatively impacted on their progression free survival (PFS), even though they had N0/N1 mediastinal staging at the time of diagnosis.

Additionally, only one patient had a surgically confirmed N2 disease not detected by EBUS-TBNA and/or mediastinoscopy. This was due to one of the major limitations of EBUS-TBNA in mediastinal staging: its inability to image and access mediastinal lymph nodes that are not adjacent to the airways, such as the prevascular nodes (3a), the subaortic and para-aortic nodes (5 and 6), and the paraesophageal and pulmonary ligament nodes (8 and 9). EUS-FNA can access stations 8 and 9; and in combination with EBUS-TBNA, the majority of mediastinum and hilar area can be assessed with, as previously referred, a higher diagnostic yield and fewer unnecessary thoracotomies.5,8,10 The practical limitation of EUS-FNA is that its transesophageal approach is usually unfamiliar to most pulmonologists, while EBUS-TBNA can be easily performed during bronchoscopy.

As shown by previous studies, the presence of an experienced pathologist during the procedure can play a crucial role since it reduces the number of inadequate samples, false-negatives and punctures with the advantage of shortening procedure time,11 and from our experience we think that the presence of ROSE in the vast majority of our procedures represents an important asset in our clinical practice. As a matter of fact, we had in our series a total of 10 inconclusive lymph nodes, corresponding to 6 patients. Four of them were staged as N2 or N3 and had an inconclusive lymph node in an inferior N station. The other two patients had only one inconclusive lymph node each, with sonographic features and dimensions not suggestive of malignancy, negative PET scan and the N0 staging was confirmed through surgical procedure.

We did not experience any major complications. Often a minor oozing of blood at the site of puncture was observed but no patient had significant bleeding, pneumothorax, or pneumomediastinum which confirms the safety of EBUS-TBNA.

ConclusionA comprehensive lung cancer staging strategy that includes EBUS-TBNA seems to be safe and effective. Our EBUS-TBNA performance and safety in this particular setting was in line with previously published reports. Mediastinoscopy did not detect any false negative nodes, questioning the need for preoperative staging of NSCLC by mediastinoscopy in clinical practice. Additionally, our study showed that, in selected patients, lung cancer diagnosis and staging are achievable with a single endoscopic technique.

Conflict of interestThe authors certify that there is no actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to this article.

Author contributionsDaniel Coutinho and Ana Oliveira conceived the project idea. Ana Oliveira, Sofia Neves and Sérgio Campainha performed all endoscopic procedures. José Miranda and Miguel Guerra performed all surgical procedures. Agostinho Sanches, David Tente and Antónia Furtado were responsible for cytopathologic analysis. Daniel Coutinho, Ana Oliveira, Sérgio Campainha and Sofia Neves collected the data and conducted the analysis. All authors interpreted and discussed the results. Daniel Coutinho and Ana Oliveira wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors must have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence must be in possession of this document.