Tuberculosis (TB) continues to be a global health concern, affecting 10 million individuals and causing 1.4 million deaths in 2019.1 The COVID-19 pandemic influenced TB diagnoses, resulting in 6.4 million new cases reported in 2021, a decline from 7.1 million in 2019.2 Portugal's TB notification rate surpasses the EU average3,4 presenting challenges in meeting the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals for TB elimination by 2035.5

Delays in TB diagnosis and treatment significantly impede effective control measures, with studies indicating an average total delay of 87.6 days, predominantly attributable to patient-related factors.6 Factors contributing to delay in Portugal include rural living, geographical barriers, poverty, low education, stigma, and limited TB awareness.7 Foreign patients, individuals with substance use disorders, and those with comorbidities endure prolonged delays.8 A comprehensive understanding of these factors is crucial for the development of effective TB control programs.

To augment our understanding of this critical issue, and to deepen the knowledge on the topic, we interviewed TB patients to gain insight into the patients` TB literacy levels, attitudes and practices behind diagnosis delay in Portugal.

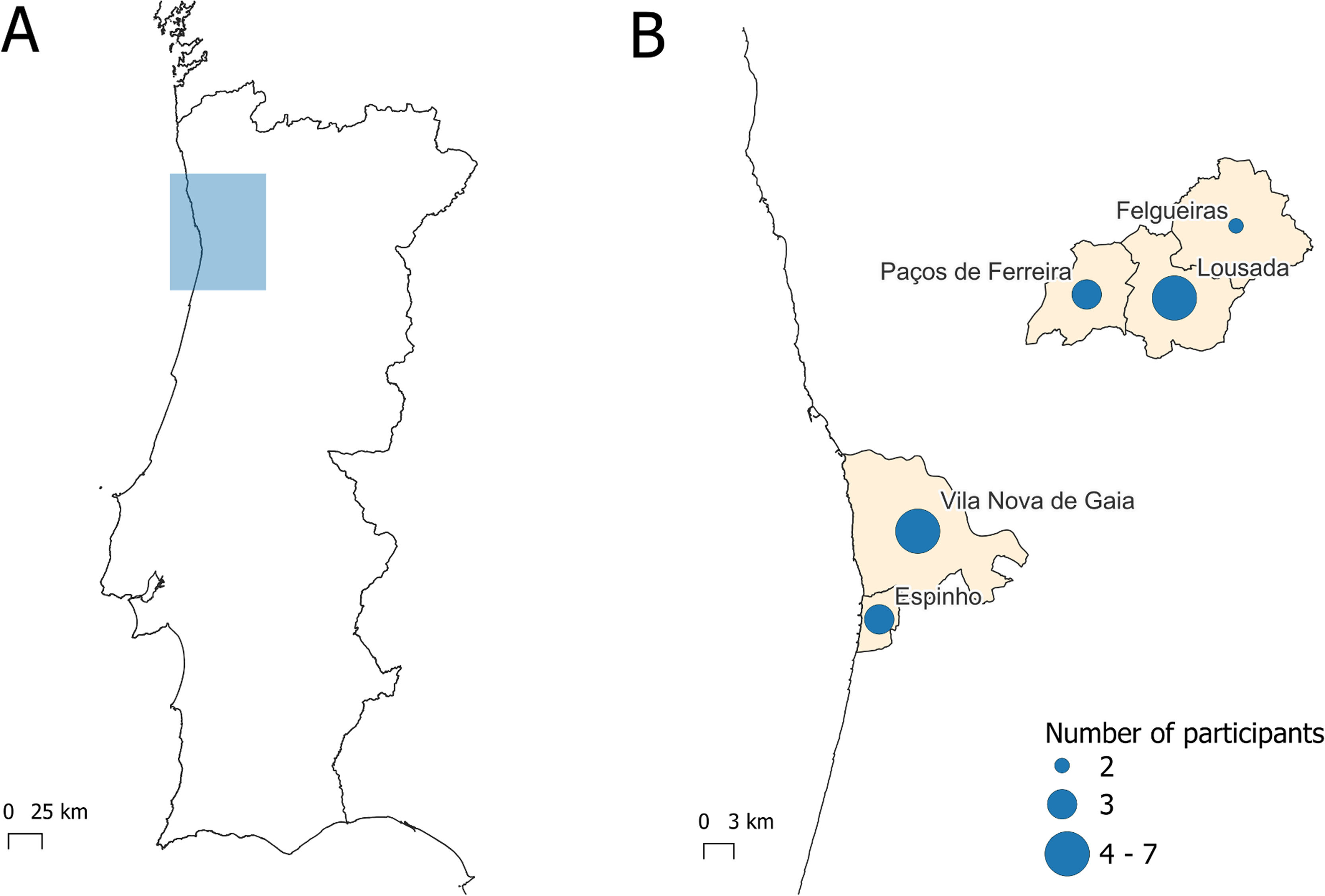

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in two Northern Portuguese cities, Paços de Ferreira (PF) and Vila Nova Gaia (VNG) (Fig. 1), encompassing both rural and urban settings and varying socioeconomic deprivation levels.9 Participants were selected through opportunistic sampling following completion of a questionnaire, excluding certain criteria. The interviews, which followed a predetermined guide, explored five main themes (Interview guide available upon request). Thematic analysis, in accordance with Braun and Clarke's protocol,10 was employed for data analysis. Two independent researchers coded the interviews, and consensus was achieved through joint review. Saturation was achieved after 22 interviews, each lasting approximately 45 min. Noteworthy quotes were selected to exemplify key themes and underwent hermeneutic translation for clarity without altering meaning.11 The study provides valuable insights into factors contributing to TB diagnosis delay from the patients' perspective.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Regional Health Administration of the North (reference CE/2022/65).

Participants predominantly comprised males (77.3 %), with mean age of 47.6 years, who were Portuguese natives (86.4 %) and 59.1 % were married/in a de facto union. Regarding the level of education, the majority (72.7 %) had up to the 2nd cycle of basic education. The majority of patients (68.2 %) had occupations of lower social status and economic power.

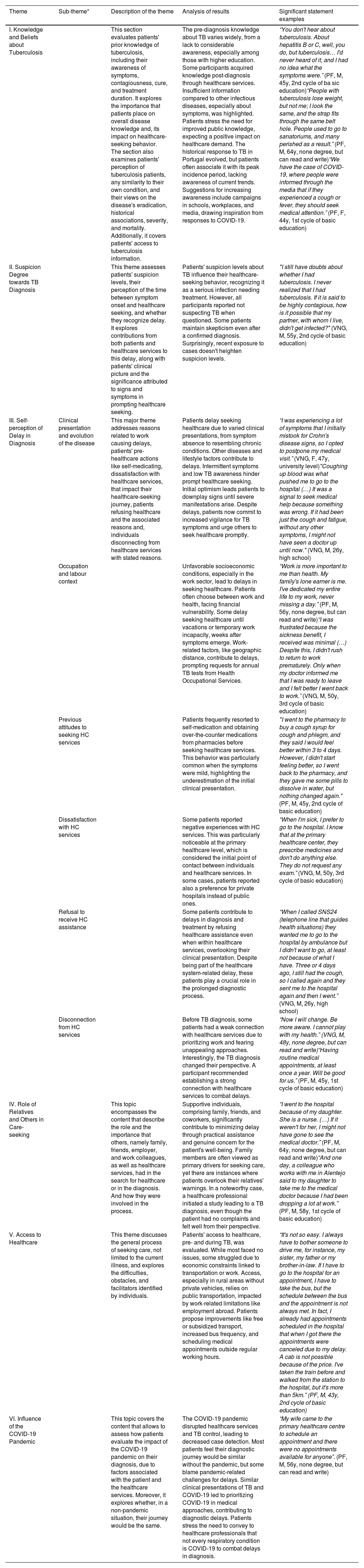

The analysis of all interviews resulted in the identification of 6 main themes: (i) knowledge and beliefs about tuberculosis; (ii) suspicion degree towards a possible diagnosis of TB; (iii) self-perception of delay in diagnosis (and its reasons); (iv) role of relatives and others in care-seeking; (v) access to healthcare; and (vi) influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the diagnosis delay. Table 1 presents each theme, sub-theme and corresponding description, the analysis of the results and quotations from participants.

Description and statements of the emerging results in the six themes identified in the thematic analysis.

| Theme | Sub-theme* | Description of the theme | Analysis of results | Significant statement examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Knowledge and Beliefs about Tuberculosis | This section evaluates patients' prior knowledge of tuberculosis, including their awareness of symptoms, contagiousness, cure, and treatment duration. It explores the importance that patients place on overall disease knowledge and, its impact on healthcare-seeking behavior. The section also examines patients' perception of tuberculosis patients, any similarity to their own condition, and their views on the disease's eradication, historical associations, severity, and mortality. Additionally, it covers patients' access to tuberculosis information. | The pre-diagnosis knowledge about TB varies widely, from a lack to considerable awareness, especially among those with higher education. Some participants acquired knowledge post-diagnosis through healthcare services. Insufficient information compared to other infectious diseases, especially about symptoms, was highlighted. Patients stress the need for improved public knowledge, expecting a positive impact on healthcare demand. The historical response to TB in Portugal evolved, but patients often associate it with its peak incidence period, lacking awareness of current trends. Suggestions for increasing awareness include campaigns in schools, workplaces, and media, drawing inspiration from responses to COVID-19. | “You don't hear about tuberculosis. About hepatitis B or C, well, you do, but tuberculosis… I'd never heard of it, and I had no idea what the symptoms were.” (PF, M, 45y, 2nd cycle of ba sic education)“People with tuberculosis lose weight, but not me; I look the same, and the strap fits through the same belt hole. People used to go to sanatoriums, and many perished as a result.” (PF, M, 64y, none degree, but can read and write)“We have the case of COVID-19, where people were informed through the media that if they experienced a cough or fever, they should seek medical attention.” (PF, F, 44y, 1st cycle of basic education) | |

| II. Suspicion Degree towards TB Diagnosis | This theme assesses patients' suspicion levels, their perception of the time between symptom onset and healthcare seeking, and whether they recognize delay. It explores contributions from both patients and healthcare services to this delay, along with patients' clinical picture and the significance attributed to signs and symptoms in prompting healthcare seeking. | Patients' suspicion levels about TB influence their healthcare-seeking behavior, recognizing it as a serious infection needing treatment. However, all participants reported not suspecting TB when questioned. Some patients maintain skepticism even after a confirmed diagnosis. Surprisingly, recent exposure to cases doesn't heighten suspicion levels. | "I still have doubts about whether I had tuberculosis. I never realized that I had tuberculosis. If it is said to be highly contagious, how is it possible that my partner, with whom I live, didn't get infected?" (VNG, M, 55y, 2nd cycle of basic education) | |

| III. Self-perception of Delay in Diagnosis | Clinical presentation and evolution of the disease | This major theme addresses reasons related to work causing delays, patients' pre-healthcare actions like self-medicating, dissatisfaction with healthcare services, that impact their healthcare-seeking journey, patients refusing healthcare and the associated reasons and, individuals disconnecting from healthcare services with stated reasons. | Patients delay seeking healthcare due to varied clinical presentations, from symptom absence to resembling chronic conditions. Other diseases and lifestyle factors contribute to delays. Intermittent symptoms and low TB awareness hinder prompt healthcare seeking. Initial optimism leads patients to downplay signs until severe manifestations arise. Despite delays, patients now commit to increased vigilance for TB symptoms and urge others to seek healthcare promptly. | “I was experiencing a lot of symptoms that I initially mistook for Crohn's disease signs, so I opted to postpone my medical visit.” (VNG, F, 47y, university level)"Coughing up blood was what pushed me to go to the hospital (…) It was a signal to seek medical help because something was wrong. If it had been just the cough and fatigue, without any other symptoms, I might not have seen a doctor up until now." (VNG, M, 26y, high school) |

| Occupation and labour context | Unfavorable socioeconomic conditions, especially in the work sector, lead to delays in seeking healthcare. Patients often choose between work and health, facing financial vulnerability. Some delay seeking healthcare until vacations or temporary work incapacity, weeks after symptoms emerge. Work-related factors, like geographic distance, contribute to delays, prompting requests for annual TB tests from Health Occupational Services. | “Work is more important to me than health. My family's lone earner is me. I've dedicated my entire life to my work, never missing a day.” (PF, M, 56y, none degree, but can read and write)“I was frustrated because the sickness benefit, I received was minimal (…) Despite this, I didn't rush to return to work prematurely. Only when my doctor informed me that I was ready to leave and I felt better I went back to work.” (VNG, M, 50y, 3rd cycle of basic education) | ||

| Previous attitudes to seeking HC services | Patients frequently resorted to self-medication and obtaining over-the-counter medications from pharmacies before seeking healthcare services. This behavior was particularly common when the symptoms were mild, highlighting the underestimation of the initial clinical presentation. | "I went to the pharmacy to buy a cough syrup for cough and phlegm, and they said I would feel better within 3 to 4 days. However, I didn't start feeling better, so I went back to the pharmacy, and they gave me some pills to dissolve in water, but nothing changed again." (PF, M, 45y, 2nd cycle of basic education) | ||

| Dissatisfaction with HC services | Some patients reported negative experiences with HC services. This was particularly noticeable at the primary healthcare level, which is considered the initial point of contact between individuals and healthcare services. In some cases, patients reported also a preference for private hospitals instead of public ones. | “When I'm sick, I prefer to go to the hospital. I know that at the primary healthcare center, they prescribe medicines and don't do anything else. They do not request any exam.” (VNG, M, 50y, 3rd cycle of basic education) | ||

| Refusal to receive HC assistance | Some patients contribute to delays in diagnosis and treatment by refusing healthcare assistance even when within healthcare services, overlooking their clinical presentation. Despite being part of the healthcare system-related delay, these patients play a crucial role in the prolonged diagnostic process. | “When I called SNS24 (telephone line that guides health situations) they wanted me to go to the hospital by ambulance but I didn't want to go, at least not because of what I have. Three or 4 days ago, I still had the cough, so I called again and they sent me to the hospital again and then I went.” (VNG, M, 26y, high school) | ||

| Disconnection from HC services | Before TB diagnosis, some patients had a weak connection with healthcare services due to prioritizing work and fearing unappealing approaches. Interestingly, the TB diagnosis changed their perspective. A participant recommended establishing a strong connection with healthcare services to combat delays. | “Now I will change. Be more aware. I cannot play with my health.” (VNG, M, 48y, none degree, but can read and write)“Having routine medical appointments, at least once a year. Will be good for us.” (PF, M, 45y, 1st cycle of basic education) | ||

| IV. Role of Relatives and Others in Care-seeking | This topic encompasses the content that describe the role and the importance that others, namely family, friends, employer, and work colleagues, as well as healthcare services, had in the search for healthcare or in the diagnosis. And how they were involved in the process. | Supportive individuals, comprising family, friends, and coworkers, significantly contribute to minimizing delay through practical assistance and genuine concern for the patient's well-being. Family members are often viewed as primary drivers for seeking care, yet there are instances where patients overlook their relatives' warnings. In a noteworthy case, a healthcare professional initiated a study leading to a TB diagnosis, even though the patient had no complaints and felt well from their perspective. | “I went to the hospital because of my daughter. She is a nurse. (…) If it weren't for her, I might not have gone to see the medical doctor.” (PF, M, 64y, none degree, but can read and write)“And one day, a colleague who works with me in Alentejo said to my daughter to take me to the medical doctor because I had been dropping a lot at work.” (PF, M, 58y, 1st cycle of basic education) | |

| V. Access to Healthcare | This theme discusses the general process of seeking care, not limited to the current illness, and explores the difficulties, obstacles, and facilitators identified by individuals. | Patients' access to healthcare, pre- and during TB, was evaluated. While most faced no issues, some struggled due to economic constraints linked to transportation or work. Access, especially in rural areas without private vehicles, relies on public transportation, impacted by work-related limitations like employment abroad. Patients propose improvements like free or subsidized transport, increased bus frequency, and scheduling medical appointments outside regular working hours. | “It's not so easy. I always have to bother someone to drive me, for instance, my sister, my father or my brother-in-law. If I have to go to the hospital for an appointment, I have to take the bus, but the schedule between the bus and the appointment is not always met. In fact, I already had appointments scheduled in the hospital that when I got there the appointments were canceled due to my delay. A cab is not possible because of the price. I've taken the train before and walked from the station to the hospital, but it's more than 5km.” (PF, M, 43y, 2nd cycle of basic education) | |

| VI. Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic | This topic covers the content that allows to assess how patients evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their diagnosis, due to factors associated with the patient and the healthcare services. Moreover, it explores whether, in a non-pandemic situation, their journey would be the same. | The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted healthcare services and TB control, leading to decreased case detection. Most patients feel their diagnostic journey would be similar without the pandemic, but some blame pandemic-related challenges for delays. Similar clinical presentations of TB and COVID-19 led to prioritizing COVID-19 in medical approaches, contributing to diagnostic delays. Patients stress the need to convey to healthcare professionals that not every respiratory condition is COVID-19 to combat delays in diagnosis. | “My wife came to the primary healthcare centre to schedule an appointment and there were no appointments available for anyone”. (PF, M, 56y, none degree, but can read and write) |

Broadly speaking, the study uncovered varied TB patient knowledge levels, ranging from awareness to ignorance pre-diagnosis. Healthcare services played a crucial role post-diagnosis, addressing limited public awareness. Despite TB severity, patients rarely suspected the disease, maintaining skepticism even after diagnosis. Perspectives on delays differed, with some attributing them to lack of awareness or visible symptoms. Supportive relatives were pivotal in care-seeking, though occasional resistance occurred. Access to healthcare posed challenges, especially in rural areas. The COVID-19 pandemic influenced some delays, with patients emphasizing the need to distinguish TB from COVID-19 clinically.

Addressing the interval between the onset of TB symptoms, clinical presentation, and diagnosis is crucial for effective TB control. This qualitative study delves into patient perspectives to uncover the factors contributing to delays in TB diagnosis. Participants exhibited limited TB knowledge and lacked suspicion before diagnosis which is consistent with previous research,7,12 emphasizing the need for targeted health education programs. Delays were attributed to HC services, maybe influenced by Portugal's low TB incidence and general practitioner familiarity issues, which is line with the recommendations of Sentís et al., (2023) on raising awareness of local clinicians.13 Participants cited various reasons for care-seeking delays, including self-management beliefs, employment conditions, and disconnection from regular healthcare. Socioeconomic factors, particularly related to employment contexts, influenced delays, with specific occupations linked to social disadvantage contributing to delayed healthcare seeking.14 Access barriers, including economic constraints and dissatisfaction with primary healthcare,15 influenced patient choices, reflecting the importance of public education efforts. Family and relative support played a crucial role in TB diagnosis, aligning with previous studies emphasizing social, emotional, and financial support.13,14 Mobility and economic barriers hindered HC service access, particularly affecting rural patients. The study also delves into patients' perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic's impact on diagnosis delay, with some reporting difficulties accessing HC services due to pandemic-related disruptions, as acknowledged in another Portuguese study.16

Interviewing TB patients revealed significant barriers to timely healthcare access. Employment conditions, transportation barriers, and dissatisfaction with healthcare services contribute to TB diagnosis delays. The COVID-19 pandemic also impacted access. Family support emerged as a protective factor. These insights can guide interventions, emphasizing education, improving access, and addressing socioeconomic challenges, informing healthcare policies globally for effective TB control.

ContributionsRaquel Duarte, Ana Aguiar, Ana Gomes and Marta Pinto formulated the initial research questions and study methodology. Marta Marques, Carla Pereira and Teresa Silva implemented the study and collected the data. Marta Pinto and Teresa Silva analyzed the data. Teresa Silva and Ana Aguiar wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors reviewed the document and approved the final version of the manuscript.